Category: Development and Construction

Understanding Security Documents in Property Development Lending

When it comes to property development funding, securing loans through various legal documents is essential to protect both the lender and the borrower. The type and nature of the documents used can vary depending on the type of loan being provided. At ASAP Finance, we specialize in providing loans for property developments, which requires a bespoke set of documents over and above the traditional term loan agreement that we are all familiar with.

These documents will set out your rights and obligations during the term of the loan, so as a developer, it is critical to understand what each document is. Not only will it help you navigate through the funding process more efficiently, but it may guide and influence your decisions during the project that will help you better manage your relationship with your lender.

In this two part blog series, we’ll explore the key security documents used in our lending practices: the Letter of Offer, Term Loan Agreement, Deed of Guarantee, General Security Agreement, Specific Security Agreement, and the Pre-sale Undertaking from a solicitor. We’ll delve into what each document is, why lenders use it, its functions, and the risks involved.

1. Letter of Offer

A Letter of Offer (LOO) is a preliminary document from the lender to the borrower outlining the basic terms and conditions of the loan before formal security documents are drafted. This document is the first binding document issued by the lender in the funding process and will be issued after terms have been negotiated.

A letter of offer will provide a clear, concise summary of the loan terms, as well as outline conditions precedent (CPs) that need to be satisfied before the lender will settle the loan.

The letter of offer allows the borrower to understand the commitment they are entering into and ensures a mutual understanding of the loan terms before proceeding with the more detailed and legally binding security documents.

Always review the letter of offer in detail; otherwise, it could lead to misunderstandings or disputes later. Consider the following:

- Review all high-level terms including facility type, loan amounts, term of the loan, interest rate, fees (including when they become payable), the commencement date, and other relevant terms.

- Review other provisions such as your ability to redraw or repay the loan facility early without incurring early repayment fees.

- Review what securities you need to provide, and ensure you can provide all securities required (this includes ensuring you’re in a position to grant a 1st registered mortgage or 1st ranking GSA as is required by almost all lenders).

- Know your CPs inside and out and liaise with consultants and other professionals to ensure you can deliver on all the CPs prior to the settlement date. While ASAP Finance offers flexibility around certain CPs, most other lenders strictly enforce these requirements

Lastly, lenders’ application fees are commonly linked to the signing of the letter of offer – irrespective of whether you fulfill the pre-settlement conditions and settle on the settlement date. This means that if you fail to satisfy the pre-settlement CPs and cannot settle, the application fees will still be payable – even if the loan does not proceed.

This re-emphasizes the importance of carefully reviewing the pre-settlement CPs and ensuring these can be satisfied prior to the settlement date.

2. Term Loan Agreement (or Facility Agreement)

A Term Loan Agreement (TLA) is a comprehensive document that outlines the terms and conditions under which the loan is provided. It will include all the details included in the letter of offer as well as additional items such as warranties, covenants, events of default, and other conditions that the borrower must adhere to during the loan term.

Lenders use term loan agreements to establish clear expectations and obligations for both parties. It serves as a legal contract that ensures the borrower understands the terms of the loan and agrees to comply with them.

Think of it as a structured framework for the loan, detailing the financial obligations of the borrower and the legal rights of each party. It also includes provisions for what happens in the event of a default, ensuring the lender has recourse if the borrower fails to meet their obligations.

Things to consider:

- Ensure the terms and conditions within the Term Loan Agreement reflect those agreed in the Letter of Offer.

- Review your covenants and undertakings in detail. Remember, your lender will have provided you the loan based on the information and representations made to them. Any inaccuracies or misrepresentations (whether intentional or otherwise) will likely be an event of default.

- Your obligations will likely extend beyond those that are purely financial. For example, most loan documents for development loans have provisions that consider scenarios where the project falls behind schedule. It is your job as a developer to ensure that the integrity of the project remains intact.

- The loan document will almost certainly have cross-default provisions, meaning that if you default on another loan, you will also be in default on this loan. Run a steady operation and don’t take your eye off the ball if you are running multiple projects.

- On that note, you should understand all events of default in detail.

3. Deed of Guarantee

A Deed of Guarantee (sometimes called a Personal Guarantee or PG) is a legal document in which a third party (the guarantor) agrees to take responsibility for the borrower’s debt if the borrower defaults on the loan.

Lenders use deeds of guarantee to mitigate the risk of borrower default. By having a guarantor, lenders have an additional layer of security, knowing that someone else will cover the debt if the borrower fails to do so.

This document ensures that the lender can recover the loan amount even if the borrower is unable to repay it. It legally binds the guarantor to fulfill the debt obligations, providing financial security to the lender.

All development facilities will typically require the main sponsors of the project to personally guarantee the loan provided to the development entity (being a company or trust).

Things to consider:

- Be prepared to personally guarantee your project. The main sponsors will almost always be asked for PGs and will need to have skin in the game – lenders don’t look favorably towards developers who do not wish to grant PGs or who are solely reliant on investor funds.

- If the borrower defaults, the guarantor must repay the loan – in this sense, you should only guarantee a loan for a project that you have direct control over and that you can control the performance of.

That wraps up Part 1 of our two-part series. In our next blog, we will explore the General Security Agreement, Specific Security Agreement, and the solicitor Pre-sales Undertaking. Stay tuned for more!

Your Building Consent has Issued – What are the Next Steps?

As a property developer, obtaining your resource and building consent is a significant milestone. However, the journey is far from over. Here’s a comprehensive guide on what to consider next to ensure your project proceeds smoothly and successfully.

1. Detailed Review of Consents

Thoroughly examine your resource consent, engineering approvals, and building consent in detail. The conditions imposed within these consents provide a roadmap to achieve Code Compliance Certificate (CCC) and titles. Failure to satisfy any conditions could jeopardize your project.

2. Firm Up Your Costs

Now is the perfect time to refine your budget. Resource consent plans often lack the detailed information needed for accurate cost estimation. With detailed plans now finalised, you can obtain more precise quotes from your builder, accounting for structural elements and other critical details.

3. Engage a Contractor

Select a contractor contractors based on experience, past performance, qualifications, licenses, and certifications. Assess their financial stability and ability to procure resources, a crucial factor highlighted during the COVID-19 pandemic. Review references and inspect previous work. Remember, the cheapest option isn’t always the best—physically visit past projects completed by the contractor to inspect quality.

4. Identify additional approvals

Besides your resource consent (RC), engineering plan approvals (EPA), and building consent (BC), there might be other permits required before you start work. These may include close approach permits, works over approvals, or vehicle crossing permits. These may be critical risk items, and failure to secure them could halt your project. For instance, agencies like AT or Vector might decline applications, leading to site shutdowns. Ensure you have a workable solution before drawing funds from your development finance lender.

5. Form a Project Control Group (PCG)

While typically associated with larger commercial projects, PCGs can benefit smaller projects too. The team usually includes the architect, builder, and yourself but can also include your engineer & surveyor. The PCG oversees the project, making crucial decisions that affect its direction, funding, and success. Regular meetings should be held to review status, address issues, and make necessary adjustments to keep the project on track.

6. Ensure No Neighbor Approvals are Required

This should be done during the due diligence phase, however it is always good to revisit this. Neighbor approvals might extend beyond the location of physical services to include site access. Certain construction methodologies may require temporary access for material delivery (e.g., via crane). Avoid such situations whenever possible. Additionally, consider how your work schedule might impact site access or interfere with other parts of the site.

7. Consider a Quantity Surveyor (QS)

Most banks require a QS to review and verify costs, material quantities, and project timelines. QS reports cover almost all project-related risks and support payment claims lodged by your contractor. Banks typically have an approved panel of QSs, so consult your lender before hiring. Note, some non-bank lenders, such as ASAP Finance may fund projects without a QS, reducing costs and simplifying the drawdown process for experienced developers.

8. Develop a sales strategy

Work with a real estate agent to optimize your sales strategy. A clear sales strategy maximizes profits and can inform decisions regarding funding partners and financial objectives. For bank funding, presales will be required necessary – in which case you will want to consider engaging an agent that specializes in selling off-plan properties. Alternatively, you might decide against presales, opting to sell on completion. In this case, a non-bank lender might be a better fit for your project and you can broaden your scope with regard to what agent you want to engage.

9. Engage a competent lawyer

A good lawyer is essential for transacting and settling property, drafting presale agreements, reviewing construction contracts and loan documents, handling sales, facilitating settlements, and managing contractual disputes.

10. Get tax advice from an accountant

Consult and accountant to optimize your project structure. Ideally, this was done before purchasing the development property. If not, consult an accountant to determine the best ownership structure, GST position, and profit distribution strategy. Many lenders offer GST facilities for progress payments, requiring timely GST return filing and a monthly GST cycle.

11. Choose the right Funding Partner!

Your choice of funding partner is as critical as choosing the right builder. If presales and cheap funding are priorities, a bank may be the best option. However, in a challenging market, meeting presale requirements can be difficult. Non-bank lenders like ASAP Finance can offer more flexibility, funding projects without presales, QS appointments, or fixed-price contracts. This can be beneficial for builders or project managers seeking greater control over their projects.

It is extremely important to conduct due diligence on your non-bank lender. Not all non-banks have the same product offerings, risk appetite, or ability to service clients. Additionally, there are nuances in how they are funded, which should be a key consideration when choosing your funding partner.

Speaking to past clients, such as property developers and builders, is a great way to gain insight into how a lender conducts business. Google reviews and client testimonials can also assist in your decision-making process.

By carefully considering these steps and engaging the right professionals, you can navigate the complexities of property development more effectively and increase the likelihood of your project’s success. We will happily review your consents and project budget free of charge to provide an indication of whether we can finance your property development, so contact us now!

Navigating New Zealand’s Property Development Landscape in 2024

As 2024 unfolds, the New Zealand property market is a confluence of challenges and opportunities for developers. The mix of data presents a complex picture, making it difficult to discern a clear market direction. This update aims to distil key facts, offering insights to navigate the shifting sands of the property development sector.

A Surge in House Price Expectations

A notable rebound in housing confidence signals rising expectations for house price increases, especially in Auckland. This trend, captured in the ASB housing confidence report for the three months leading to January 2024, hints at a broader national optimism. It suggests we might be on the cusp of recovery and growth, moving away from the recent downturn.

Listings Reach All-time High

February 2024 witnessed an unprecedented surge in new listings, with Realestate.co.nz reporting a 45% year-on-year increase to 11,788 new residential listings. Auckland’s market saw a significant influx, marking an 11-year high with 5,382 properties listed with Barfoot and Thompson. This abundance puts buyers firmly in the driver’s seat, heralding a shift towards a buyers’ market despite underlying positive pricing trends.

The Interest Rate Conundrum

Interest rates remain a pivotal area of focus, with mixed expectations about their future trajectory. While there’s apprehension about potential hikes, there’s also a growing sentiment that we might be nearing the peak. This uncertain interest rate landscape requires developers to engage in strategic financial planning more than ever. With mortgage advisors and agents noting an increase in first-home buyers with pre-approvals, a moderate interest rate scenario could spur a notable uptick in market activity.

Economic Indicators and Market Activity

The economic backdrop has its complexities, with Stats NZ indicating a recession in the latter half of last year. Despite this, the housing market displays resilience, with early 2024 showing healthy year-on-year house price growth. This dynamism points to a stabilising market, ripe for growth against the backdrop of increasing population and persistent housing shortages.

Regional Dynamics: A Diverse Story

The recovery narrative is not uniform across New Zealand. Regions like Otago exhibit strong housing value increases, contrasting with areas experiencing different median sale price trends. This diversity underscores the importance of nuanced strategies for developers, tailored to specific local market conditions.

New Consents Decline

The end of 2023 saw a sharp drop in new home consents, although this follows a period of record highs. This fluctuation suggests a normalisation of the consenting environment rather than a downturn. The true impact of new consents on the market remains to be seen, serving more as an indicator of developer optimism than a direct measure of upcoming construction activity.

Refined Strategic Considerations for Developers

Given the mixed signals from the property market in 2024, developers must navigate cautiously, armed with strategies that address current trends and anticipate future shifts. Here’s how these strategies can be tailored to the unique landscape described:

Navigating a Buyers’ Market with Flexible Sales Strategies

With listings at an all-time high and buyers in the driving seat, developers should consider flexible pricing and sales strategies to stand out in a crowded market. This might include offering purchase incentives, customizable new build options, or flexible financing arrangements to entice discerning buyers.

Capitalizing on the Surge in House Price Expectations

Despite the broader buyers’ market, areas like Auckland are seeing a surge in house price expectations. Developers in these regions could prioritize projects that align with this optimism, focusing on properties that cater to market segments demonstrating the most robust growth prospects.

Adjusting to the Interest Rate Landscape

With the potential for interest rate stabilization, developers should remain vigilant and prepare for various financial scenarios. This includes securing favorable loan terms now, while also staying prepared for any shifts that could affect buyer affordability and, consequently, demand for new developments. Maintaining a good relationship with your non-bank lender may afford you more flexibility should the need arise.

Economic Recession vs. Market Resilience

The apparent disconnect between the broader economy’s performance and the housing market’s resilience suggests developers need a dual focus. They should not only track macroeconomic indicators but also deeply understand the housing market’s unique dynamics, adjusting project timelines and investment focuses accordingly.

Responding to Changes in New Consents

Following a peak, the drop in new consents indicates a potential normalization of the market. Developers should use this period to reassess their project pipelines, prioritizing developments that meet current market needs while also preparing for future demand rebounds.

Addressing the GDP Per Capita Decline

Understanding the impact of a falling GDP per person on market segments is critical. Developers might need to pivot towards more affordable housing projects or adjust their offerings to remain appealing to a potentially cost-sensitive buyer base.

Targeting Untapped Regional Markets

With regions like Otago showing strong growth, developers should consider expanding their focus beyond traditionally popular areas. Detailed market research can identify other regions with high growth potential, allowing for diversified investment and reduced risk.

Emphasizing Quality and Value in Development Projects

In a market characterised by an abundance of options for buyers, emphasising the quality and unique value propositions of your developments can help differentiate them. This includes focusing on sustainable building practices, innovative design, and community integration that adds tangible value to potential buyers.

Forward-Looking Strategy

As 2024 continues to unfold, developers face a complex environment shaped by economic uncertainties, shifting buyer dynamics, and regional disparities. By adopting a forward-looking strategy that addresses these nuances, developers can confidently navigate the current landscape. Staying adaptable, informed, and responsive to market changes will be key to seizing opportunities and overcoming challenges in New Zealand’s property development sector.

Need bespoke funding from New Zealand’s market-leading development lender? Contact us

Capitalised Interest Loans in Development Finance

Capitalised Interest Loans

In the dynamic realm of development finance, capitalised interest loans serve as a strategic option for lenders and developers alike, offering flexibility to the client and risk mitigation for the lender. Let’s delve into the core features of capitalised interest loans and understand why it is the preferred repayment type in the world of development finance.

Understanding Capitalised Interest Loans

Monthly Interest, Capitalised: Capitalised interest loans break away from the traditional repayment model. Instead of developers managing monthly interest expenses, the interest is ‘capitalised’ onto the principal amount each month. The entire repayment, covering both principal and accumulated interest, happens when the loan matures.

Assessment of exit strategy: When a capitalised interest repayment structure is adopted, the lender relies on the client’s ability to “exit” or repay the loan in full upon maturity to earn their interest (and recover the principal sum). In this sense, development funders place a greater emphasis on “exit strategy” as opposed to “cash flow” when a cap interest structure is adopted. In most instances, this will be the eventual sale of the properties upon the projects completion. However it could also be by way of refinance to another lender. Understanding the dynamics of loan repayment structures is essential for both lenders and developers.

Risk Mitigation: A loan facility is comprised of a principal sum, and capitalised interest provision. If a capitalised interest repayment structure is being used:

-

The lender retains the capitalised interest within their facility. Doing so means that the lender knows what their total exposure (LVR) will be upon maturity of the loan.

-

A loan facility is made up of multiple components. Assuming that the Facility Limit of a loan is fixed, allowing for capitalised interest within the loan facility will reduce the principal sum available to the client.

The Dynamics of Development Loans in New Zealand

Cost-to-Complete Basis: In New Zealand, property developments are predominantly funded on a cost-to-complete basis. This means that the lenders structure loans to ensure that they always have sufficient funds in their loan facility to complete the project. As a project progresses, the property value is enhanced and the “cost to complete” the project decreases. This creates a surplus within the loan facility, allowing lenders to release funds to the client, recognising the value contributed to the site.

Capitalised Interest as a Project Cost: Finance costs, an integral part of any project budget; thus “interest” needs to be retained by the lender within their loan facility. Strict adoption of funding on a cost-to-complete basis will see most lenders insist on interest being capitalised for property developments. Lenders will forecast what they expect the likely interest cost will be for the term of the loan and include a provision within the loan facility.

Loan term and final LVR position: Lenders providing a capitalised interest loan do so for a specific term and based on a forecast facility limit. When the end of the term is reached, the loan will reach the facility limit. If a loan extension is required, further capitalised interest (and fees) will need to be provided. This means that the facility limit will need to increase. However, doing so will increase the LVR. If the lender is unwilling to take on further risk, the borrower will need to pre-pay interest and fees for the extended term. This is one of the reasons why lenders pay very careful attention to the development program when setting up the loan facility and during the construction phase. Potential delays can ultimately increase finance costs and increase the LVR for the loan.

Tailored Solutions for Property Developers

Development Income: Property developers, often without traditional income streams, rely on project completion and sale. Capitalised interest loans align with this income structure, allowing developers to defer interest payments until the project is sold, simplifying their financial commitments, and alleviating the financial burdens during critical construction and development phases.

Minimising Capitalised Interest Expense: Unlike lender fees, which apply to the facility limit, interest is only charged on the drawn balance of the loan. To reduce interest expenses, consider minimising the initial cash advance. This may involve paying off existing mortgages or restructuring debt away from the development asset, ensuring an unencumbered property before setting up the loan. However, it’s essential to acknowledge the trade-off – reducing debt may cut costs but could impact the return on equity for the project.

Capitalised Interest Loans: A Win-Win for Property Developers and Lenders

In the diverse landscape of development finance, capitalised interest loans emerge as the preferred repayment method for lenders and property developers. These development loans empower developers to prioritize cash flows toward projects while concurrently serving as an effective risk management tool for lenders.

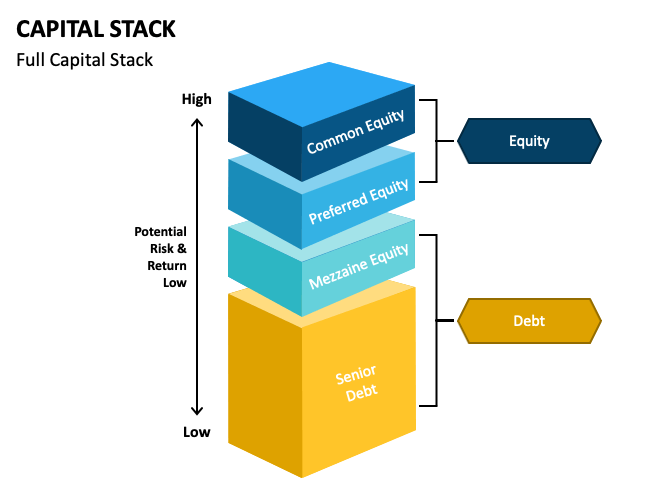

The Capital Stack – What is it and why does it matter?

The Capital Stack

When it comes to property development, one of the most important concepts to understand is the capital stack. In simple terms, the capital stack refers to the different sources of financing that are used to fund a property development project. These sources of financing can include equity, debt, and other types of financing.

Understanding the capital stack is crucial for property developers, as it helps them to determine the most appropriate financing structure for their project. By carefully balancing the different sources of financing in their capital stack, developers can optimise their overall cost of capital relative to their expected return on investment.

Let’s take a closer look at the different components of a typical capital stack:

Senior Debt

Senior debt is typically the first layer of financing in a capital stack – such facilities are commonly provided by banks but also include non-bank lenders and finance companies (such as ASAP Finance).

Senior debt takes priority above all other financing including mezzanine debt and equity – priority is secured by way of a first ranking mortgage registered on the certificate of title of the property. Other securities such as General Security Agreements, Deeds of Assignment, Deeds of Priority and Subordination, Specific Security Agreements and Personal Guarantees are also common in development funding. These securities ensure the lender has the first claim to any proceeds of sale resulting from the development.

Lending criteria for senior debt facilities can vary greatly, however almost all will have loan-to-value and loan-to-cost requirements. Minimum equity contributions are also common, ensuring developers have skin in the game.

The priority status of senior debt makes it less risky, but as a result it also commands a lower return for the lender.

Mezzanine (Junior) Debt

Mezzanine debt or Junior debt is a type of financing that sits between senior debt and equity in the capital stack.

It is typically secured by way of a second registered mortgage (behind an existing first) or in some instances may be unsecured.

Because it ranks lower in terms of priority, mezzanine debt is higher risk lending and carries a higher interest rate than that of senior debt, however it is cheaper than equity funding.

Equity

Equity represents the capital that is invested in a project by its owners or investors. Equity investors take on the highest risk in a project, as they are typically the last to be repaid and have no guarantee of a return on their investment. However, they also have the potential to earn the highest returns if the project is successful. If a developer is short of their own equity, they can look to raise equity from investors however given the risks, it is also typically the most expensive form of financing.

Preferred Equity

Preferred equity is a type of financing that sits between mezzanine debt and common equity in the capital stack. It typically carries a fixed rate of return and priority over common equity investors in terms of repayment.

Common Equity

Common equity represents the ownership of the property development project. Common equity investors take on the highest risk in a project, as they are typically the last to be repaid and have no guarantee of a return on their investment. However, they also have the potential to earn the highest returns if the project is successful.

Why Does This Matter?

By carefully balancing the different sources of financing in their capital stack, property developers can create a financing structure that is both cost-effective and tailored to their specific needs. For example, a developer may choose to use more of equity in their capital stack to maximise returns, or more leverage (senior debt + mezz) if they are looking to maximise total returns on equity across multiple projects.

Overall, understanding the capital stack is crucial for property developers looking for property development funding. By carefully considering the different sources of financing available to them and creating a well-structured capital stack, developers can minimize their overall cost of capital and maximize their potential returns.

10 Questions From Your Development Funder (Pt. 2)

10 Questions Lenders Ask When Funding Property Developments (Part 2)

Welcome to part two of our blog series, where we explore the top 10 questions lenders and finance companies in Auckland will ask during the application process. The previous blog post covered the first five questions lenders will ask. In this instalment, we will delve into questions 6-10 which span everything from your initial funding requirements to GST implications. Let’s take a closer look!

(6) What is your funding requirement?

For obvious reasons, your development funder or non-bank lender needs to know how much funding you require. This can normally be broken into two components.

- The Initial Advance (used to assist with a refinance of an existing mortgage, or an initial cash advance towards land settlement); and

- The Progress Payment Facility (to be allocated toward project costs on a cost-to-complete basis)

Most development funders will lend on a first-mortgage basis only, meaning any existing mortgage must be refinanced as part of the finance package. You must consider this part of your ‘funding requirement’.

Lenders will assess your funding requirement against internal guidelines for loan-to-value (LTV) and loan-to-cost (LTC) ratios. It is important to remember that each project is assessed on its own merit and these ratios may vary depending on the location and type of project.

Be prepared to discuss your project budget at a high level. These include things such as land acquisition costs, construction costs, and subdivision costs. Lenders will assess square meter rates and whether your construction construction costs are realistic. Anything that doesn’t quite stack up may raise a potential red flag for your project, including low construction costs or inflated land prices.

When applying for development funding with ASAP Finance, we thoroughly review your project budget in detail to ensure that you have included all costs required to complete the project. This should include allowances for: professional fees, council fees (such as development constitutions), utility connections, civil works, and construction as well as an appropriate contingency.

(7) What is the development programme?

Lenders will want to know how long the development is expected to take, as this will impact their risk assessment. A longer development timeline may increase the lender’s risk, while a shorter timeline may decrease it.

Lenders will use this information when considering an appropriate loan term. However, this is something you the developer should also consider. Should you accept a loan term that is shorter than your development programme you expose yourself to opportunistic lenders who may look to re-price your loan or provide unfavourable loan extension terms. Keep in mind that finding a new lender mid-construction is extremely difficult so your options will be limited.

(8) What is your plan for repaying the loan (exit strategy)?

Whether you plan to sell the completed development or retain the properties, discussing your plan for repaying the loan is crucial at the start of the funding process.

Do you intend to retain the properties after completion? You lender will need to see that you have the financial capacity to meet the long-term mortgage requirements of traditional lenders such as major banks or ‘near bank’ lending institutions.

If you plan to sell the units, your lender will want to know what your sales strategy will be and if you have any pre-sales prior to drawing down. Your sales strategy should encompass whom you intend to market and sell the properties, likely asking prices and when you plan to start marketing the development. Any presales should be bank quality as we discussed in our guide to exit strategies.

Holding or selling the properties on completion will also have implication on the way GST is treat and internal LVR calculation for the lender.

(9) Are you GST registered/have you and will you be claiming GST?

The majority of the projects we fund are built to sell. Thus most of our clients will be GST registered and will have claimed GST against the purchase price of the land purchase and will similarly be claiming GST on construction costs. This also means that GST will be payable when you sell down the units.

If GST is payable on the sale of the houses on completion, we need to deduct GST from our end values when calculating LVRs. For example, if we decided the maximum LVR for a project is 70% against an as-if complete value of $1,000,000 including GST, then the maximum loan facility we could offer would be c.$608,000. [Calculated as $1,000,000 / 1.15 (GST) x 70%].

If a client GST registered (and is claiming GST) we can fund projects on a GST-exclusive basis, using a separate GST facility to fund the GST. A GST Facility is a revolving credit facility that is used to exclusively fund the GST portion of a Progress Payment. Funds drawn down from this facility to pay GST are repaid by the IRD in the form of a GST Refund. Using a GST Facility enables a lender to fund a project on a GST-exclusive basis, at the same time ensuring that all contractors are paid in full (the GST inclusive amount). In other words, using a GST Facility reduces the amount you need to borrow from a lender by approximately 15% (less the GST facility itself).

(10) Who have you engaged as your main contractor/who are your key project consultants?

In our experience, the most successful property developers are those who have built the best team. This spans everything from solicitors, accountants, contractors and other project consultants.

As a lender, we will be interested in understanding your consultants’ and contractors’ qualifications, experience, and track record of completing similar projects on time and on budget.

Having a team with relevant qualifications, insurance and licenses, it will demonstrate to the lender that your project is managed by experienced professionals who are able to effectively oversee the development and navigate any potential challenges that may arise.

Having a reputable, experienced and well-respected project team will not only help ensure the project is completed on time and on budget, but it also reduces risk for the lender, increasing your chances of securing funding.

Be prepared

Securing funding for your property development can be challenging, but understanding what information is relevant to your lender can make the process less daunting. By understanding and learning how to address common questions lenders ask, you can increase your chances of securing funding. When considering your application, lenders look at a variety of factors such as location, development nature, project team, exit strategy and more. By being aware of these factors and knowing how they align with your project goals will enable you to present a strong lending proposition. Remember, a lender wants to invest in feasible projects backed by a good team and have a good ROI. Keep these in mind so you can increase your chances of success.

10 Questions From Your Development Funder (Pt.1)

10 Questions Lenders Ask When Funding Property Developments (Part 1)

Securing funding for your property development can be challenging , but understanding what information is relevant to your lender can make the process less daunting. This blog post will be the first in a two-part series where we break down some of the critical questions you can expect a lender or property finance company to ask, so that you can better prepare for your next development funding pitch.

Please note that this is not an exhaustive list nor a comprehensive guide to all the questions your lender may ask. Instead, we are aiming to provide insight into some of the more common questions lenders pose, and the reasoning behind why they are relevant. Lenders use these discussion points to determine whether your project fits their credit criteria.

Here are some of the questions you can expect, along with the reasoning behind why they are crucial:

(1) Where is the project located/what is the property address?

Lenders will often have different criteria based on geographic locations. ASAP Finance prefers to offer property developments loans for projects in main urban centres such as Auckland, Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington, Christchurch and Queenstown. This is primarily due to the greater liquidity (transaction volume) in these markets, making it easier for clients to a sell property and repay their loan(s).

The specific property address reveals more detailed property attributes, such as whether the property is in a desirable area, site aspect, contour of the land, location to services and amenities, and underlying zoning. As lenders, we must look out for any property attributes that make funding your project more challenging, such as a poor location or lack of access to services.

(2) Who owns the property/what entity will be undertaking the development?

The property owner tells us who the borrower will be. Most clients undertake projects under a Limited Liability Company (LLC). However we also fund projects where the development is being undertaken under a trust, limited partnership, or personal name. We recommend seeking professional advice from your accountant concerning the best structure to use for your project.

If the project is to be undertaken by an LLC or other investment vehicle, we will want the director and key sponsors to guarantee the loan. Understanding the parties involved in the transaction, and the role that each party will play, is something we will cover with you as part of the application process.

Properties owned under personal names can be an issue. This is because there may be CCCFA implications if the property is owner-occupied. Many non-bank lenders do not write CCCFA loans, which means if the property is owned under a personal name and is owner-occupied, we will not be able to assist you with your project.

More complex structures such as trusts and partnerships have a high threshold for AML, and may also require a more detailed explanation as to how partners are introducing equity in the project and the source of those funds.

(3) What is the nature of the project, i.e. what are you proposing to build?

Of course, each lender needs to know what they are funding, but understanding what you are proposing to build also gives us further insight into the overall feasibility of your project. We will be assessing:

- The complexity of your proposed development and relative risk weighting (e.g., residential townhouses, apartment complexes, and subdivisions all have different risk attributes).

- Whether your product is suited to the location you are proposing to build in.

- The expected demand for your product in that location.

- Whether your costings accurately reflect what you are proposing to build.

(4) What stage of the development lifecycle are you in? Have all necessary consents been obtained to begin the project?

Lenders generally priortise build-ready transactions (ie. ready to draw down) versus those further away from starting construction.

Most funders will only provide full development facilities when they know construction can begin shortly thereafter. Approving a loan that is too far away from drawdown increases the risk of the market changing between the approval and when construction starts.

Rule of thumb: apply for development funding when you have your resource consent, engineering approvals, and your building consent has been lodged (but is yet to be approved).

(5) Do you have any previous experience in property development?

We will want to know if you have any previous experience in property development, as this can provide insight into your ability to complete a project successfully. Lenders will look for a track record of completed developments and assess your ability to complete the project successfully. Building a CV to showcase recently completed projects is an excellent way to demonstrate your capabilities. For those new to development, focus on building your development team – to a certain extent, the experience can be bought!

Next steps

Securing funding for your property development can be a complex process, but understanding the relevant information your lender can make it less so. This blog post is a two-part series that aims to break down some critical questions you can expect your lender to ask. Stay tuned, for part two where we explore further questions your lender may ask.

Settlement Defaults – What You Need To Know

It is well established that settlement default risk increases during downturns in the property market. A settlement default occurs when a purchaser fails to complete the purchase of a property according to the terms of a binding sale and purchase agreement. At ASAP, we have personally witnessed an increase in the number of purchasers attempting to back out of such agreements due to recent declines in property prices, particularly presales entered into during the height of the market (late 2021). In light of this, we thought it timely to discuss the options available to developers in the event of a purchaser default.

ADLS Agreement for sale and purchase

The ‘Agreement for Sale and Purchase’ (ASP) comes in many forms however the Auckland District Law Society (ADLS) is by far the most common form of ASP used to transfer ownership of property in New Zealand. The ADLS ASP underpins much of the wealth transfer in New Zealand and the contract law surrounding this agreement is robust and fiercely protected with obligations under ASPs strictly enforced by courts. If a purchaser enters into an unconditional agreement to purchase a property, they are expected to follow through with the purchase.

In the unfortunate event of a purchaser default, the vendor has multiple options available to them under the standard form REINZ/ADLS ASP.

Specific performance

The first option is to seek a court order for specific performance, which would obligate the purchaser to complete the purchase. While this may seem like a logical solution, it is not always feasible. If the purchaser is unable to settle due to a lack of funds, a court order will not change their ability to meet their settlement obligation. Additionally, obtaining a court order can be time-consuming and costly, with no guarantee of success.

Nonetheless, it is perhaps one of the most underrated ways to ensure the performance of a purchaser. Having a court order against you (as a defaulting purchaser) immediately impacts your credit rating and will greatly impair your ability to conduct business in the future. If the purchaser genuinely has the ability to settle, then seeking specific performance may be your best bet. In our experience, a purchaser who feigns an inability to settle will often find a way to settle once face with a court order.

Cancelling the agreement

The second option is for the vendor to cancel the agreement and retain any deposit paid by the purchaser (not exceeding 10% of the purchase price), and/or to sue the purchaser for damages.

It is important for vendors to receive a deposit of at least 10% from purchasers to have this as a viable option. If there is nil deposit, or if the deposit is small, the vendor’s only recourse may be through the courts, which makes it easier for the purchaser to walk away from their contract if the vendor is not prepared to litigate. If the deposit amount is greater, be sure to amend Clause 11.4(b)(i) of the general terms to allow full retention of the deposit.

If you elect to seek damages through the courts, keep in mind that you cannot be put in a better position than you would have been if the original contract had been completed. In this sense, recovery of damages typically includes (but not limited to) the recovery of;

- Any loss incurred on any bona fide resale (you cannot make a claim simply based on a reduced valuation). The resale contract also needs to be entered into within one year from the date when the original purchaser was due to settle.

- Interest on the unpaid portion of the purchase price at the interest rate for late settlement from the settlement date.

- All costs and expenses reasonably incurred in any resale or attempted resale; and

- All outgoings (other than interest) on or maintenance expenses in respect of the property from the settlement date to the settlement of a resale.

The above damages are just some of the examples and all damages claimable at common law or in equity can be recovered by the vendor.

Re-marketing the property

The third option is for the vendor to remarket the property to third parties without cancelling the existing agreement. Clause 11.4(2) of the ADLS ASP allows the vendor to re-market the property – should the vendor enter into a subsequent agreement to sell the property during this process, the original agreement will automatically be cancelled. This may allow you to adopt a multi-strategy approach such as seeking specific performance while at the same time, seeking another party to purchase the property.

Sale to a company

If the purchaser is a company that is still trading, the vendor may seek a statutory demand from the courts as a means of pressuring the company to settle the purchase. If the company as purchaser, owns any other properties (perhaps as part of a wider property portfolio) then a statutory demand can be highly effective.

If a statutory demand is not complied with within 15 working days of it being served, then the company will be presumed to be unable to pay its debts and the vendor (as a creditor) can then rely on this presumption and apply to the High Court to have the company put into liquidation. This will impact the company’s wider portfolio so most will have no choice but to settle the purchase.

Lastly, we recommend considering inserting a personal guarantee clause into the further terms of your ASP. This means that a company that does not own any other assets, will not be able to liquidate and walk away from the sale without personally implicating the directors of the company.

Recommendations

- Have a robust ASP. Selling off-plan is a unique way to sell property. Seek input from both real estate agents (that excel in selling off plan) and lawyers who specialise in property development. This will ensure that you have the appropriate clauses inserted into your ASP as further terms of sale (and can also help with building out a wider marketing strategy).

- Make sure you have a deposit of at least 10% from purchasers.

- Undertake due diligence on purchasers and ensure they have the financial capacity to perform. Inform your real estate agent that you expect them to undertake due diligence on potential buyers. It is also best to avoid speculators and highly geared investors who are more likely to get into trouble.

- Should purchasers indicate that they may be unable to settle, let them know early about your intention to issue a settlement notice. You should also inform them that legal action may follow. While some may see this as an unreasonable and aggressive tactic, signalling is an effective negotiation tool that preserves you position.

- If a purchaser does default on their obligation to settle – act promptly. Serve a settlement notice as soon as possible as detailed above. Again, this preserves your position and gives the purchaser 12 working days to complete settlement after which you can decide on whether you want to exercise other available remedies.

- Obtain expert legal advice.

ASAP Finance is an expert non-bank lender specialising in construction and development finance. Get in touch to explore funding for your next project.

Exit strategies

Formulating a robust exit strategy is a critical part of the development process. When assessing an application for a development loan, the credibility of a clients’ proposed exit strategy will be reviewed and assessed in detail.

There are several ways a developer can exit a construction loan – the most common strategies being:

- to sell the development down, or

- to hold (and refinance any residual debt).

No matter the strategy, a lender’s comfort around this area of the transaction is paramount as this is how they expect to be repaid. Failure to clearly demonstrate how funds will be repaid and how you can execute on your strategy will likely result in the funding application being declined.

Learn how to create an exit strategy properly below.

Recycling Profits

Selling down completed stock (be it dwellings or sections) to realise profits is the most common exit strategy property developers adopt. This strategy enables profits to be recycled from one project into another upon completion. This “rinse and repeat” model enables developers to quickly scale their business and grow profits.

Many lenders will lend more aggressively against a ‘sales strategy’. This is because a ‘refinance’ (or ‘hold’) strategy requires the residual debt upon completion of the project to be refinanced. This means that any initial development funding provided by the initial lender cannot exceed an amount the developer will be able to borrower in the refinance market.

Refinancing requires the developer to meet servicing criteria (at a future point in time) which is largely unknown when they start construction. Because lending criteria (and interest rates) are constantly in flux, development lenders will be conservative when providing funding to clients to intend to hold their product.

As a result of the above, most lenders will lend more aggressively when the developer adopts a ‘sale strategy’. This means that selling down properties is a less capital-intensive compared to holding – not only because they can obtain greater leverage but also because the developer’s equity is not tied into the project over the long-term. Therefor, a developer’s return on equity tends to be higher over the short term.

Of course, there is an argument for both exit strategies as over the long term, holding can generate capital gain that can exceed any short-term gain generated through development.

Pre-selling & Lending Criteria

Mainstream lenders such as banks typically require a certain number of pre-sales as a pre-condition to funding construction. In today’s environment, most NZ banks require between 100-130% presale cover to ensure that their debt can be repaid in full upon completion of the project. One of the reasons that (some) banks insist upon a pre-sale cover greater than their debt facility (say 130%) is to ensure that their debt can still be repaid should some purchasers default.

In contrast non-bank lenders have more flexible terms and can fund projects with no (or a limited number of) presales. They also have greater flexibility when determining what constitutes a ‘qualifying presale’.

If you have decided to obtain pre-sales, our suggestion is to always seek ‘bank’ quality pre-sales where possible (regardless of the individual lender’s requirements). Bank quality presales can be typically defined as follows.

- Unconditional (subject only to the issuance of title and CCC)

- Independent contracts sold through an agent

- No related party sales

- Minimum 10% deposit paid (for NZ residents, 20% for non-NZ residents) and held in a solicitors trust account

- Terms consistent with the proposed plans for the project

- Appropriate sunset dates are usually +12 months after the expected completion date

- Sales to individuals (as opposed to a company or trust). If a sale is to a company or a trust then obtain a supporting guarantee from the Directors or Trustees.

- Avoid multiple sales to the same party (as they will typically not be accepted)

Following the above principles will put you in a good place to obtain funding from most lenders.

Should You Pre-sell?

Pre-selling has its perks when it comes to risk management however making such a decision will likely have broader implications for your project, particularly its profitability.

Below we look at some key points developers should consider when making this decision:

Risk mitigation

This one’s obvious – there is a reason that lenders insist on pre-sales. Pre-selling locks in revenue and protects your downside in the event of a decline in property prices. It also establishes a robust (often bankable) exit strategy via a watertight contractual arrangement. Selling at the end of a project will expose the developers to changes in market conditions leading us to our next point…the property cycle.

The property market is cyclical

A firm grasp on what stage of the property cycle we are in will enable us to make more informed decisions when it comes to risk management and risk mitigation. Pre-selling in the growth phase will likely result in you leaving money on the table. A good example is a client who was building two-bedroom townhouses in Epsom, Auckland in 2020. Feedback from real estate agents (and an RV) had suggested an end value of $1.0m per unit. However, our client could see that the market was taking off and was convinced that his product would present better on completion. He decided not to pre-sell, instead listing his properties when they were nearing completion. Between starting construction and completion, the market had moved substantially and our client sold all ten units for greater than $1,150k per unit, a +$1.5M gain in revenue for the project.

Cost Escalations

What is the likelihood of cost escalations during construction? In recent years, property prices have skyrocketed; however, so too have construction costs. This created an interesting predicament for some developers who had sold off-plan. By pre-selling, you are locking in your revenue. This means that any increase in cost (no matter how minor) will directly impact profitability. We all saw the news article in 2021 where developers were trying to renege or renegotiate on pre-sale contracts. This is because construction cost escalation during the build had eroded their profits. In the meantime, property prices were well above their initial presale prices, giving them the incentive to try cancel presales to recapture a project’s margin. In such circumstances, ensuring that construction costs are fixed before starting a project, and retaining/holding back some stock are just some ways to mitigate the impact of escalating construction costs.

Off-plan discount

It is commonly accepted that selling off-plan/before the project has been completed results in the developer selling at a slight discount to market (up to 5% of the purchase price). This can be for various reasons including uncertainty about what will be delivered, time delays, hesitancy on what direction the market may head and so on. However, this is not a blanket rule. Some developers take advantage of this using comprehensive marketing packs and high-quality renders to upsell their development.

Supply and demand: understanding what competing stock is planned for delivery (and when) should inform your sales exit strategy. You may decide to sell on completion if there is no competing stock. If there is lots of competing stock, then it will likely be harder to sell on completion and days on the market will increase. If you are fully drawn on a construction facility, holding costs will quickly erode your development margin. In this instance, pre-selling (at least some) will enable you to reduce debt and de-risk your project.

Price validation: while agents and valuer’s provide an incredibly valuable service, even they can be wrong. If you are building an unusual typology or intend on building a product that is new for the area, then pre-selling will enable to you to test the price point of your product. This will underline revenue assumptions in your project feasibility and allow you to move forward with your build with confidence.

Developing a Sales Strategy

There is no one size fits all approach when it comes to developing a sales strategy. For this reason, instead of detailing an effective sales strategy we have posed some questions which we encourage all our clients to consider before launching their sales campaign.

A good sales agent will help develop a comprehensive sales strategy, and thus we suggest obtaining multiple proposals from various agencies (similar to a tender process) before committing to any one agent.

- Who is the best sales agent to represent you – is there a particular person or agency who would be best suited to sell your product?

- What is the best fee proposal to incentivise your sales agent?

- When is the best time to commence marketing?

- Are you going to pre-sell off plan or sell closer to completion?

- How much stock do you want to release and when? Are you looking to sell 100% of your product before commencing construction or simply sell as many as you need to unlock funding.

- Will one typology be harder or easier to sell compared to another?

- Will selling one product first create a price floor or ceiling for unsold stock?

- How are you going to market your product i.e. what sales channels are you going to use?

Don’t get caught out

Undertaking a development without an exit strategy in place not only undermines your ability to obtain funding but can severely impact the viability of your project.

Pre-sales protect your downside; however, it can come at a cost. Deciding to sell on completion is still a viable strategy, so long as you clearly demonstrate how you will execute this and its rationale.

Being fully drawn on a construction loan facility with no exit in place will result in you incurring unnecessary holding costs which can quickly erode a project’s profit.

Be prepared on how to create and exit strategy; talk to ASAP Finance about funding your next project.

The Subdivision Process

Subdivisions are a common feature in property development. The subdivision process is where a parcel of land is divided into one or more parcels. When complete, a unique Record of Title will issue for each new parcel of land.

In our experience, some of the most common issues in development pertain to an inability to obtain titles (linked to your subdivision consent) or Code of Compliance (which is linked to your building consent).

In this blog post we look at some of the more important stages of the subdivision process to highlight and hopefully mitigate critical risks associated with the process.

Council Planning Rules

The zoning rules set out in a council’s Unitary or District Plan (such as the Auckland Unitary Plan) will dictate how a given property can be used or developed. These rules stipulate whether subdividing your property is a permitted, controlled, restricted discretionary, discretionary, non-complying or prohibited activity. Each zone has slightly different rules and design guidelines that must be met for you to subdivide your property.

For example, different zones will have varying requirements for a site’s density, lot sizes, vehicular access, and more. This process is managed through the Resource Consent Application.

Consenting process

The two main types of consents associated with property development are (i) a Land Use Consent, which will allow you to undertake a type of activity on your land, and (ii) a Subdivision Consent which allows you to subdivide the property into separate parcels. A land use consent and a subdivision consent are two separate consents; however, they can be applied for together as a bundled consent.

The RC application involves preparing plans and consultant reports that validate the proposed design and its impact on the wider environments. Common reports that support an RC application include an AEE report (Assessment of Environments Effects), Geotech reports, Traffic reports, Engineering reports and more.

In this respect, engaging the right consultants and taking time to plan and validate your project carefully before lodging for consent will ultimately save you time and money. Skilled planners and architect’s will have in-depth knowledge of RMA planning rules and regulations. They should be able to prepare designs in such a manner that gives your application a high chance of getting approved.

Obtaining consent for your project – without dramatically changing the initial design will ensure that that assumptions made when preparing your feasibility study will hold true. If council forces you to change your plans, it may compromise the viability of your project. For example, if you can only build five houses instead of six, it will impact your project feasibility. This risk is known as consenting risk and one of the reasons non-bank lenders lend more conservatively against (development) properties that do not have an approved resource consent in place.

Section 92 Response

Once an RC application is submitted, council will review the information provided. They will then likely issue a Request for Further Information (RFI). This RFI process, known as a Section 92 (s92) request, is where council seeks additional information to identify any potential adverse effects on the environment from the proposed activity (should they issue the consent). Your consultants will then file a response addressing their questions and countering their concerns. A s92 request is a significant milestone as it provides insight into councils view on key issues and ultimately the likelihood of the consents approval.

Draft Conditions & Final Approvals

When council is satisfied with a resource consent application, they will the issue draft conditions. These will ultimately become the final conditions that will have to be satisfied for to you give effect to your resource consent. In this sense it is an important opportunity for you and your consultants object to any conditions that are unreasonable or overly onerous.

Most consent conditions will pertain to ensuring that the work is completed in accordance with the plans submitted to council, and that upon completion of the project all the additional lots are fully services and connected to local infrastructure.

Skilled consultants will know those conditions that are reasonable, and those that are not. Unreasonable conditions and additional compliance can quickly escalate a project costs and result in delays during construction.

EPA and Building Consent

In addition to your RC, you will require other council approvals before a project can commence. For example, in Auckland, most development will require an Engineering Plan Approval (or “EPA”) that permits engineering works to be undertaken for critical infrastructure (that will ultimately vest with Council or other government bodies such as Watercare). This typically relates to infrastructure that will become ‘public’ and under the control and responsibility of Council however it can also include items like retaining walls and vehicle crossings.

The final piece of the puzzle is Building Consent which applies to the structure. All building work in New Zealand must comply with the Building Code (with very few exceptions), hence almost all projects require a Building Consent.

While Building Consents are commonly associated with dwellings; retaining walls and other structures may require a separate Building Consent – such items may be linked to your EPA and therefore the underlying subdivision.

Physical works, S223 & S224(c)

A subdivision consent alone does not give you new records of title. To apply for new titles through Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) you first need to obtain Section 223 and Section 224(c) certificates (as referred to in the RMA.

As previously mentioned, your subdivision consent will have several conditions that need to be satisfied – such conditions are broken into two parts.

- Conditions you must complete before a Section 223 certificate can be issued, and

- Conditions you must complete before a Section 224(c) certificate can be issued.

S223

S223 conditions relate to the preparation of the subdivision scheme plan and associated legal documents (such as easements or land covenants) that will be endorsed on the survey plan (and title).

This work scan be undertaken with minimal to no physical works been completed on site. This should be undertaken as early as possible to prevent delays with obtaining titles.

Applicants have five years to lodge a Survey Plan with Council. This plan is a detailed plan prepared by a registered surveyor showing the boundaries, areas, and if relevant any easements and covenants that need to be prepared. If the plan is in accordance with what was approved by Council as part of the subdivision consent, then a Section 223 certificate approval will be signed.

Once this has been signed by Council the plan may then be lodged with Land Information New Zealand (LINZ) for approval.

S224(c)

Section 224(c) conditions pertain to completing physical works on the site. These conditions commonly relate to the installation of services and infrastructure to each (wastewater, stormwater, power, fiber etc.). The newly created lots will also need to have accessways formed.

Understanding what work must complete before you can obtain 224c is very important. It can inform decision around the construction programme and how you chose to deliver your project. For example, you may decide to install all the services and pour the driveway before commencing the vertical construction to ensure that title delivery is ahead of Code of Compliance.

A Section 224(c) certificate is a final approval from Council relaying that all conditions of the subdivision consent have been complied with and all works are complete. A s224c application will set out each condition of the approved resource consent and have commentary as to how compliance has been achieved. This application should be accompanied by the relevant 224(c) certificate for signing.

Processing times of s223 and s224(c) certificates vary but sometimes it can take months to issue. Council officers and engineers may need to undertake further site inspections or require additional documentation; hence most delays associated with titles occurs at this stage.

As is always the case in development funding, delays at a project’s end will be more costly. This is because you will be near fully drawn on a construction facility incurring significant holding costs. This is why skilled developers place great weight on obtaining titles early. Lastly, before you can uplift your s224(c) certificate, you will need to pay any development contribution as required by the council.

LINZ

Once you have the s223 and s224(c) (with any easements, consent notices etc.) you are all set to lodge for titles. This is done through LINZ who will process the information and issue titles for the newly created lots. This process is not done through council and is a separate application process. In our experience, LINZ processing time can vary between 5 to 40 working days. Yet another reason to obtain titles early.

ASAP Finance is a leader in property finance in New Zealand. Get in touch today for all your property finance needs.