Category: Development and Construction

Property Development Due Diligence – Neighbour Consents

In our previous blog we explored key factors property developers should consider when undertaking pre-purchase due diligence. In this blog, we revisit some of those concepts with a particular focus on neighbour consents and approvals.

In our experience, neighbours will object to having a property development occur in their back yard. This is not surprising as even the most considered projects will impinge on previously enjoyed privacy due to newer higher density zoning rules being rolled out by various councils. Furthermore, all projects will have a certain amount of disturbance resulting from noise and dust during the construction period.

In most cases, neighbours have no say as to whether a project can proceed (so long as the development complies with relevant zoning rules). However, failing to undertake proper due diligence may result in you being entirely reliant on your neighbour to proceed with your development. If your neighbour refuses, it may prevent you from obtaining development funding.

Infrastructure and services

Identifying how a project is going to connect to surrounding infrastructure is a critical component of due diligence. Subdividing a property requires all newly created lot needs to be fully serviced – this includes the installation of water, wastewater, stormwater, power, telecoms, and fibre.

In an ideal world, these services will be readily available from the road frontage. In some instances, however, the closest connection points will be on your neighbour’s property. Naturally, you will not be able to access this infrastructure without your neighbour’s consent. Should they decline, at best you will be forced to consider other (likely more expensive) solutions to connect services to your site, or at worst you will be prevented from proceeding with the project at all.

In such instances where there are no viable alternative connection points available to you, you can make an application to council requesting them to undertake these works on your behalf. This application is made in accordance with Section 181 of the Local Government Act 2002. This is a long, protracted process whereby neighbours are still afforded a right of objection under the act. Should parties continue to disagree, then the matter will ultimately be heard before the courts. In our experience, councils are very reluctant to go down this route and we do not consider it a viable or cost-effective solution.

Shared rights of way

As infill developments have increased with popularity, issues relating to shared rights of way have become more common. A starting point for shared rights of way is to assume that you will not be able to subdivide the property (as of right).

Properties that have a shared ROW, typically have corresponding easements that grant the respective owners a right to access their property by crossing over the easement area. As a developer, the extent to which you can rely on an access easement to subdivide a rear lot will depend the increased burden on the servient land. If the neighbouring landowner claims that the use of easement is above and beyond its initial intended use, they may have a case to stop or prevent works from proceeding. At the very least, you may face a long-protracted battle through the courts costing time and money.

In addition, most resource consents will require you to upgrade the driveway and vehicle crossing – this will likely result in the ROW being blocked while construction occurs, breaching essential terms in the easement instrument.

Zoning & Overlays

Simply put, a property’s zoning will dictate what you can use the property for, and what you can build on the property. As a developer, a high-level understanding of relevant zoning rules will enable you to quickly assess (i) how many lots a site can yield, and (ii) potential typologies (both of which will inform revenue assumptions in your feasibility).

This is not something that should be taken lightly. Incorrect revenue assumptions will undermine a project’s profitability. It is important that expert advice is sought – both your architect and planner can give guidance around more complex planning rules such as: height in relation to boundary (HIRB), minimum set back and outlook provisions, and more.

In addition to planning rules, local councils provide data as to other special property features. This may include special character areas, flood plains, overland flow paths, erosion & slips, wind risk and subsidence, protected trees and more. Each of these special features will impact the developability of you project – for example, a property located in a flood plain may require you to raise the floor levels of a proposed building. Overland flow paths may dictate the positioning of certain build footprints. Erosion and slip risks may dictate a specific foundation design. As you can see, planning is a complex area that often traverses other area of expertise (such as engineering).

Site access & air rights

Small sites, or those with unusual dimensions should be treated with care – there will likely be technical challenges that need to be resolved when it comes to access and construction methodology.

This includes addressing how plant, equipment and materials will be delivered onto the site and how they will move around the site during the construction period. Keep in mind that you need to operate within the boundaries of your property at all times.

High density apartment developments that require a tower crane need to consider neighbouring air rights. The crane will need enough room to operate and maneuver without crossing over neighbouring boundaries. Health and safety aside, breaching a neighbour’s air space (or ‘air rights’) is an act of trespass, similar to traversing over a neighbour’s land without consent. It is common for apartment development to buy air rights to operate a crane over neighbouring properties during the construction period.

Fencing

Fencing is a better understood aspect of development, and the Fencing Act clearly sets out who is responsible for what when it comes to installing a boundary fence. As with any works on neighbouring land, both parties need to agree as to what is to occur. Best practice is to engage with your neighbour early to ensure that you have enough to work through the process should the parties not be able to agree to form of boundary fence.

Of note, the cost of installing a new fence is to be shared between you and the neighbour, on the basis that the proposed fence is “reasonably satisfactory” for the purpose it is intended to serve. Legal arguments aside, we are of the opinion that the developer should bear the brunt of the cost for the upgrade – after all, they developer can expense the cost and will also be making a margin on the product. This is a small price to pay for the inconvenience and disruption caused to the neighbour during construction.

Agreeing to pay for the cost of a new fence, can be an effective negotiation tool to get the neighbour to agree to the form of fencing that is to be erected. If you cannot reach an agreement then there is a formal process that can be followed which involves; issuing a “fencing notice”, and if agreement cannot be reach; mediation, arbitration and formal legal proceedings may follow. As a developer, the aim should be to avoid lengthy legal disputes at all costs.

Tips to avoid your project stalling

- Avoid situations where you are reliant on a neighbour’s consent. In our experience, neighbours are not naturally inclined to work with you. As they see it, they will be better off without the nuisance of development occurring next to them. Those who are willing to work with you, will likely require compensation.

- Should your neighbour agree to works occurring on their land ensure that it is correctly documented. Standard form agreements/consent forms provided by councils are not sufficient (primarily because they are revocable). Formal neighbour agreements should:

- identify what work is to occur, when it will occur, and who will be undertaking it;

- provide the developer a time to undertake work during which the consent is non-revocable;

- require the neighbour to notify any successive owners of their property of your agreement, such that it remains enforceable even if they sell the property. This covers you in the event your neighbour sells, and the new owner is less agreeable to works commencing.

- Even though council may have approved a resource consent, engineering plans or building consent does not mean that you have a right to undertake work required if said consent requires work on, under or above someone else’s land. We have seen many a consent that cannot be practically delivered.

- Any works set to be undertaken on neighbouring land should be done first. Neighbours who were once amenable tend to change their mind when they realise the size and scale of the development that is due to occur next to them. For example, complete the drainage before commencing other works.

- While many disagreements between neighbours can resolved through the courts, the main factor to consider is time. Even when you are legally within your rights, the time it takes for you to achieve the desired outcome should be a key factor when deciding what course of action to take. As a developer, you will continue to incur holding (finance) costs and long drawn-out court battles can quickly erode any project margin.

ASAP Finance are leaders in property finance in New Zealand. Get in touch today for all your property finance needs.

Property Development Due Diligence

Thorough due diligence is an essential risk mitigation strategy that all purchasers need to undertake before acquiring a property. For developers, it is an opportunity to test a project’s viability and identify key risk items that may impede or prevent a project’s completion and you ability to obtain finance.

Due diligence should include an investigation of both the physical and ‘paper’ attributes of the property spanning everything from the contour of the site, relevant zoning rules, and the certificate of title.

In this article we focus on site specific considerations, noting that general market research is equally as important in delivering a successful product to market. This would include researching local demographics, pricing factors, design preferences and more.

Let’s take a look as some fundamental areas of due diligence that you, the developer should be reviewing.

Traffic & Transport

Site accessibility, safety, road frontage, and general surrounding traffic flow will all contribute to the final design. Developing a property that significantly increases traffic flow in an area that already has high levels of traffic flow will be commensurately more difficult.

Keep in mind that a transport assessment reports form a key part of resource consent applications. Local councils will need to see that your project is designed in a way that meets minimum safety standards, and that the resulting increase in traffic flows will not have a negative impact on the immediate environment (among other things).

Availability of Services

Understanding where utility connection points are located and how you may connect to them is an essential part of due diligence. Review connection points for stormwater, wastewater, general water, telecoms, power, gas and fibre and more. In an ideal world, services will be located nearby and not require complex solutions – however this is often not the case.

What to look out for

- Services that are located far away or on main public transport routes (that may require complex Traffic Management Plans)

- Services that require extensive upgrades – this may include wastewater or stormwater upgrades, transformer upgrades or undergrounding overhead powerlines.

- Services that require access to a neighbour’s property – neighbours can be inherently difficult to deal with. If given a choice, most are inclined to not agree to a substantial development occurring next to their back yard.

- Sites that have a challenging contour or sit below the road – such sites may issues with invert levels. Incorrect invert levels may require you to install pumps on site or may even prevent development entirely.

What happens if services aren’t available

It is not a given that existing council infrastructure will have sufficient capacity to accommodate additional connections, despite zoning rules allowing the increased density!

Insufficient network capacity may require you to:

- extensively upgrade (council) assets before connecting,

- reduce the number of units you can build, or

- in severe cases, prevent you from developing at all.

An engineer’s report should quickly identify any capacity constraints you may face with existing infrastructure as well identify the best means to connect to said assets.

Note, if any of the above factors reduce the total number of dwellings you can build on the site (which drives the projects revenue), then you will reconsider what you are willing to pay for the site.

Zoning & Overlays

Simply put, a property’s zoning will dictate what you can use the property for, and what you can build on theproperty. As a developer, a high-level understanding of relevant zoning rules will enable you to quickly assess:

- How many lots a site can yield, an

- Potential typologies (both of which will inform revenue assumptions in your feasibility).

Why zoning matters

What you build will impact what you can sell for ie. your revenue. Incorrect revenue assumptions will undermine a project’s profitability. It is important that expert advice is sought – both your architect and planner can give guidance around more complex planning rules such as: height in relation to boundary (HIRB), minimum set back and outlook provisions, and more.

Other special features

In addition to planning rules, local councils provide data as to other special property features. This may include special character areas, flood plains, overland flow paths, erosion & slips, wind risk and subsidence, protected trees and more. Each of these special features will impact the developability of you project – for example, a property located in a flood plain may require you to raise the floor levels of a proposed building. Overland flow paths may dictate the positioning of certain build footprints. Erosion and slip risks may dictate a specific foundation design. As you can see, planning is a complex area that often traverses other area of expertise (such as engineering).

Improvements

Improvements on a site are often removed to maximise the sites full development potential. Hence understanding the cost to remove such improvements needs to be considered. This will likely be influenced by the size of the structure and type of material used.

It is important to identify any contaminants (such as asbestos) that may increase demolition costs. If you are retaining the improvements, then it is critical to ensure that building is structurally sound and fit for purpose.

Land Area & Yield

Consider the gross area of the property. Council planning rules often have maximum site coverage rules which will influence the density of any proposed development. It is also important to consider what the net developable area is—as some areas of a property may not be developable due to its topography, restrictive easements or covenants. It may transpire that the net developable area of the property is significantly less than the gross area stated on the record of title. This is important as it net developable area will drive how many subdivided lots you yield from a site.

Topography

Considerations here extend beyond the sites contour and relevant cost assumptions for earthworks and retaining. It almost a given that steep sites will be more costly to develop. An often overlooked aspect of development is how a sites topography impacts the design and installation of stormwater and wastewater assets.

Most stormwater and wastewater connections rely on a gravity-feed systems, so sites that fall away from main connections points will require pumps to assist with flow. In some instances, pumping may not be feasible, rendering the entire site un-developable.

Lastly, the site contour will also likely impact stormwater runoff & overland flow paths (if any). Check the council overlays as these elements will likely need to be factored into your projects design.

Vegetation

Vegetation is really no different to existing buildings or structures. You may wish to retain some vegetation as a means of adding character or value to the project, however it likely that some (if not all) of the existing vegetation will need to be removed to enable re-development.

Reviewing council overlays will reveal any protected trees or native bush areas on your property that may prevent or limit re-development. An allowance for an arborist and landscape architect should be included in your budget, in addition to landscaping soft costs.

Lastly, observe trees which border your property as there may be setbacks requirements from neighbouring tree drip-lines.

Soil & Ground Conditions

Soil and ground conditions are one of the greatest unknowns for any development. While desktop analysis can shed some light on likely ground conditions, invasive testing is the best way to mitigate ground risk. Even then, invasive testing done a ‘sample’ basis meaning that ground risk cannot be eliminated entirely, and contingency sums should be allowed for in the budget specifically for this purpose.

Geotech findings should identify any site remediation that may be required as well as make recommendations to the foundation designs. Keep in mind that a formal Geotech report is required for most resource/building consent applications.

Right of Way (ROW) & Access

Subdividing a property that is located down a shared Right of Way (ROW) can be complex. While ROW’s are put in place to ensure legal access, using an easement for anything other than its intended use may give rise to dispute. For example, subdividing a property that results in an increase in the number of vehicles that use a ROW could be considered use of the easement in a materially different way.

Furthermore, such subdivisions usually require the driveway to be upgraded (which may require neighbours consent). While subdivision may still be possible, it is best to avoid instances where conflict is a likely outcome.

Properties that have shared driveways should be treated with extreme care – where relevant, contractual agreements put in place to ensure access.

In addition to rights of way, consider how easy it is for the contract to access and work on the site? Can trucks access the site to deliver material? How will you neighbours be affected? These are some some of the questions that need to be answered.

Land Information Memorandum (Lim)

A LIM report is issued by a local territorial authority and is a summary of all the information council holds on file in relation to the property (for a more complete record of information you can considering a Property File).

Most of the information found in a LIM is available from public sources includes building and resource consents, zoning and planning information, special property features, rates information and more. That said, the way the information is packaged makes it convenient and essential reading as part of any due diligence.

Record of Title & Legal Considerations

Legal checks predominantly relate to your properties ‘record of title’ (previously certificate of title). This is an extremely important part of due diligence that requires careful attention – errors or incorrect assumptions made here may entirely prevent your development from proceeding.

The record of title proves the ownership of the land and details any rights or restrictions that apply to the land.

A high level review will quickly reveal the type of ownership interest (freehold, leasehold etc), the land area, legal description, DP plan, and more. Perhaps one of the most important part of a title review lies in establishing what other registered interests are attached to the land.

Interest in the Land

This includes registered interest such as easements, land covenants, consent notices as well as unregistered interests. It is important to carefully review all interests (‘instruments’) noted on the title as they can dramatically affect the development feasibility of a site.

Easements

Easements grant the right to do something on someone else’s land or burden your land by granting a right to another landowner. When planning a development understanding what rights (or burdens) are placed on your property will have material impact on a project design. Keep in mind that you are often not able to obstruct or build over easement areas granted to other parties over your land.

Land covenants

Land covenants are rules that affect how you may use the land. The covenant may make you do something (positive covenants); or prevent you from doing something (restrictive covenants). Example of land covenants include preventing the ability to further subdivide the property, enforcing minimum building floor areas for new dwellings (common in new subdivision) and enforcing specific design guidelines.

Limited as to Parcels

Do a quick check to ensure the property is not ‘limited as to parcels’. A title that is ‘limited as to parcels’ means when the title was first issued, a guaranteed title could not be issued due to insufficient survey information or someone else being in adverse possession of part of the title. Cadastral survey data will need to be provided to LINZ to establish your properties boundaries before it will issue a guaranteed title. For obvious reasons, it is critical to establish your properties boundaries before commencing a development.

Conclusion

Due diligence should inform your investment decision – it is an opportunity to systematically refine revenue and cost assumptions relating to your project, giving you an more accurate idea as to the overall profitability of the project and ultimately its viability. Site attributes that (i) increase costs, or (ii) reduce revenue, will ultimately reduce the projects profitability and subsequently the amount you should pay for the site.

Due diligence is not only about the now – it is also about paving a pathway forward. Uncovering potential issues before construction commences give you time to adjust and improve your development plan to ensure the best chance of securing development funding.

As Abraham Lincoln famously said; “Give me six hours to chop down a tree and I will spend the first four sharpening the axe.”

Property Development Fund Flows and Sector Risk

By now, most property developers will be well aware of the credit crunch sweeping through the development finance sector. With limited funds at their disposal, development finance lenders are allocating funds on a preferential basis with a focus on existing client relationships – at the same time, lending criteria is adjusting. Lower LVRs and higher equity requirements are becoming a feature of property development funding approvals. There has also been a noticeable shift away from certain sectors of the residential market. In this blog, we break down how funding supply is reducing risk appetite and why certain sectors are falling out of favour in the realm of property finance in New Zealand.

Supply and demand

Adjustments in credit criteria can have a significant impact on how funds flow through the market.

Recently, a tightening in main bank credit criteria has resulted in an excess demand for funds in the non-bank market. This has occurred at a time when new building consents are at record highs and a strong pipeline of work is making its way through the system. The non-bank sector was quick to absorb the initial demand however it now appears that lenders are operating at near capacity (specifically within the construction and

development finance sector). As a result, non-bank lenders have similarly started to tighten.

It is commonly accepted that when lenders have excess funds, they are incentivised to loosen credit criteria. This is because lending specialists have (fixed) holding costsin the form of line fees or distributions to investors. This encourages lenders to quickly deploy funds to earn a return on their money, as required to maximise profitability. In contrast, a lender that is ‘fully lent’ is already maximising its profits and thus will be less inclined to write loans outside of standard credit policy.

It is worth noting that this supply demand imbalance is occurring at the same time as the development sector experiences a number of headwinds – something that we have extensively covered in previous blogs. So how are lenders adjusting their potential property development ffunding for the long term and the short term?

Sector Risk

In the residential property market, there are a plethora of sub-sectors, each with different risk profiles. Below we break down the distinguishing features of each sector in an attempt to shed light on why lenders are adjusting their risk profiles.

Standard Residential Property

In the property finance sector, completed houses are viewed as one of the ‘safer’ forms of lending. This market is characterised by high levels of liquidity with demand buoyed by both the owner-occupied and investor markets. This means that lenders can enter and exit positions with relative ease.

High levels of liquidity also support price transparency across the market. Most residential houses can also be quickly rented to generate holding income which can offset debt servicing requirements.

From a financing standpoint, because there is no ‘drawdown’ component to these loans (as with development loans), lenders earn an immediate return on their money. Furthermore, there is minimal ongoing management required. For the above reasons, lenders will often prefer lending in this sector rather than for property development lending.

Development & Construction Loans

Development finance has always been viewed as a riskier lending proposition than lending against standard residential properties. This is due to a variety of reasons including:

- Direct links to the construction sector which is prone to boom-and-bust cycles

- Exposure to commodity prices/raw materials

- Execution risk (including construction risk), development is a speciality skill set that requires expertise from all parties, including the developer, the contractor, and project consultants.

- Time delay between the commencement of a project and the expected completions date (the market can change during this period making a previously feasible project no longer viable

- Projects must be taken to completion to realise the value

Given the above, lenders will naturally look to reduce their exposure to this market when funds are limited compared to other lending propositions.

Land banks & Bare Land:

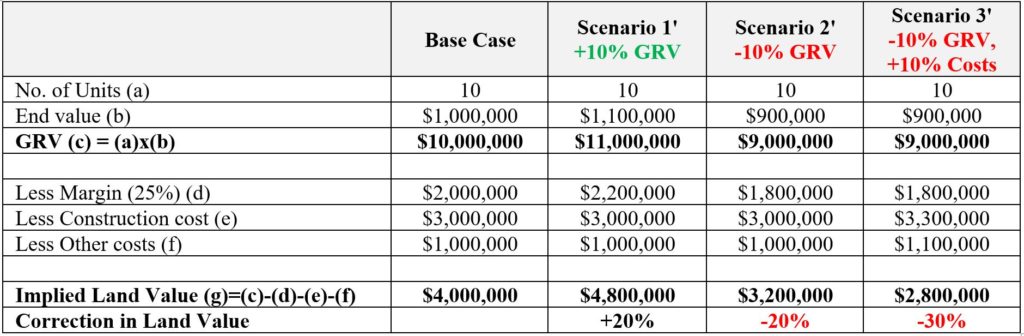

Bare land is considered a higher risk lending proposition – this is primarily due to how quickly land prices can adjust in response to minor adjustments across the broader housing market.

Higher-end values for completed housing stock have been instrumental in driving up land prices across the country over the past few years. This is because the GRV (gross realisable value) of a project is directly correlated to the underlying value of the land (i.e. what a developer can pay for the land). Any change to a project’s GRV has an outsized impact on underlying land value.

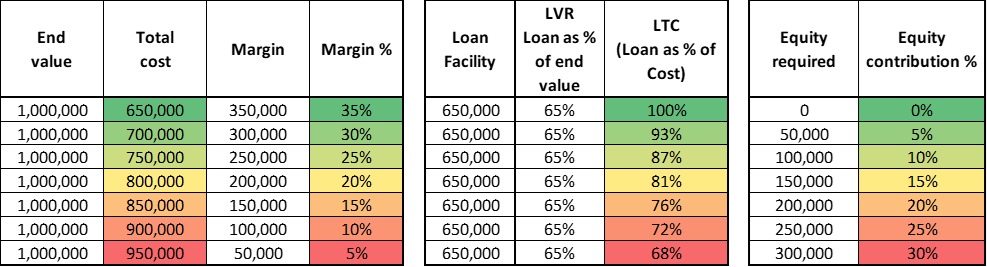

Take the below scenario where a developer is building 10 houses, which he expects to sell for $1m. This implies a GRV of $10m (being 10 units x $1M in revenue per house).

Now let’s assume the value of the completed units increases by 10% in line with the market. That is the GRV increases by $1M to $11M (GRV). In this instance, if the developer is happy with a 25% net return, and his costs are fixed, a 10% increase in end value implies the developer can pay an additional 20% for the underlying land. So, in this scenario, a 10% increase in GRV results in a 20% increase in land value.

The same principle applies to downward corrections, as can be seen in the below table. This is why development finance is a riskier proposition than funding completed houses.

Land corrects more aggressively in a downturn; hence you will find that most lenders have stricter lending criteria for land with the potential to develop. Lastly, the below table assumes that costs are fixed – increasing costs add further pressure on the as-is value of development land.

Looking ahead

Recently, we have seen over-trading in development land with an apparent disconnect between the underlying economic value of land prices relative to what people have been paying. In the near term, we expect to see a moderate softening in this market as some developers come to the realisation that their project is no longer feasible. Those that can afford to hold, will simply defer the project until such time as it does become feasible. While some will likely be forced to sell – presenting opportunities for others.

ASAP Finance are leaders in in New Zealand. Get in touch today for all your property finance needs.

Insurance and risk mitigation

As a builder or developer, you will know that working in construction means being vulnerable to all kinds of risks, many of which can result in compensation claims or financial loss. The inherently unpredictable and dangerous nature of the work means that you, your employees, sub-contractors, and members of the public are all vulnerable to physical accidents as well as property damage.

Insurance is an effective mechanism for transferring the risk (and associated financial loss) should something go wrong. In return for accepting this risk, you pay a premium to your insurer. However, not all policies are the same.

As a developer or builder, it is essential to know what insurance policies provide the best protection to your project. Furthermore, all lenders will require you to have appropriate insunraac cover before putting in place a development finance solution. In this blog, we explore some critical construction insurance policies and why they are important.

Public Liability Insurance

Public liability insurance is a policy that covers compensation claims arising from personal injury or accidental damage or loss to someone else’s property. Most construction work takes place on a third-party property, so it is no surprise that contractors have a high level of exposure to public liability risk.

The three main levels of public liability cover are $5m, $10m, and $20m, with the higher levels of cover attracting the higher premiums—noting that cover in place should be reflective of the nature and scale of the contracts being entered. While specific insurance policies vary between providers, most include cover for legal defence costs in addition to damages or compensations awarded by the court.

Public liability insurance does not cover damages relating to the “contract works”—when a builder enters into a construction contract, it is the builder’s responsibility to complete the work in accordance with the contract. Therefore, any damage that the builder causes is their responsibility to resolve, until such time as the contract is complete. In other words, because there is no loss to a third party, the builder will not be able to file a public liability claim but may be able to claim under a contract works policy if the damage is accidental.

Lastly, liability resulting from faulty workmanship is generally excluded from public liability claims. As a result, when damage does occur, a common issue is ascertaining whether the damage is the result of an accident or faulty workmanship. Some providers offer cover for a contractor’s liability resulting from faulty workmanship as a policy add-on (in return for an increased premium); this is something that you should discuss with your contractor.

Why is Public Liability Insurance important?

While public liability insurance is not mandatory by law, most construction contracts will require the builder and sub-contractors to have public liability insurance. Similarly, lenders will require public liability insurance to be in place prior to allowing funds to be drawn down from a construction facility.

Take an example where a contractor is doing earthworks and accidentally damages an underground power cable, or a scenario where contaminants are accidentally discharged into a neighbour’s stormwater line. The costs to remediate such damage has the potential to be financially crippling for the contractor. And as a developer, you need to know that your contractor has the financial capacity to successfully deliver your project.

Why is Public Liability Insurance important?

While public liability insurance is not mandatory by law, most construction contracts will require the builder and sub-contractors to have public liability insurance. Similarly, lenders will require public liability insurance to be in place prior to allowing funds to be drawn down from a construction facility.

Take an example where a contractor is doing earthworks and accidentally damages an underground power cable, or a scenario where contaminants are accidentally discharged into a neighbour’s stormwater line. The costs to remediate such damage has the potential to be financially crippling for the contractor. And as a developer, you need to know that your contractor has the financial capacity to successfully deliver your project.

Contract Works Insurance

Contract works insurance, also known as “builder’s risk insurance”, is an insurance policy that provides cover for sudden and accidental losses to the contract works. Policies can include both new builds and renovations of existing structures and will generally cover damage resulting from fire, theft, vandalism, construction collapse, some natural disasters, and other accidental damage to the contract works.

Almost all construction contracts will require contract works insurance to be put in place before works can commence. You can also be certain that your lender will require contract works insurance to be in place (and in an acceptable form) prior to drawing down from any construction finance loan facility.

Key things to consider when implementing a contract works policy

When putting in place contract works insurance, there are a few key things to consider:

Insured sum: The insured sum is the maximum amount the insurer will pay you (less any excess payable) in the event of a total loss. For a partial loss, the insurer will pay a fair proportion of the insured sum. For this reason, it is extremely important that the insured sum is sufficient to cover the cost of replacing or remediating the damaged property.

For example, if the contract value to build a house is NZD$1,000,000, then you would expect the insured sum to be no less than this amount. You should also consider what additional allowances need to be made for demolition, professional fees, and construction costs escalation when considering the insured sum. Keep in mind that for commercial contracts, the insured sum should always be plus GST.

Should you under-insure your project, then any funds paid on a successful claim will not be sufficient to remediate the property in full. This will require you to bridge any shortfall in funding, putting the entire project at risk.

Cover period: Your policy should be in place for however long it takes to complete the “contract works”. In other words, the period of cover should match the construction period in your development programme. Furthermore, irrespective of the expiry date on your policy, contract works cover typically ceases upon the earlier of the following happenings:

- Practical completion

- When someone starts using the building (such as an owner or tenant)

- When 95% of the budget is spent (for spec builds)

- The end date on the policy

To clarify, practical completion can occur weeks before a code of compliance certificate is issued by a relevant territorial authority, during which your property may not be insured. It is essential that you engage with your insurer to understand when your policy expires and to have a general fire and risk policy arranged for when your contract works insurance expires. After all, any loan facility provided to you by your lender will require your property to be insured at all times; failure to arrange the proper insurance may result in a “technical default.” To avoid this, insurers provide optional “completion cover” add-ons, which cover you for a specified period after the construction period or contract period is over.

Interested Parties: An interested party is someone that has a financial interest in your property. For contact works, this will usually be your lender; after all, it is likely their funds are being used to complete the development. Most lenders will require their interest noted on the policy; if so, advise your broker before putting the policy in place, as they will need to update the certificate of currency.

Exclusions: Contract works insurance covers costs arising from all kinds of accidental damages to the contract works. However, there are certain kinds of damages that are typically excluded. Below we explore some of these in more detail.

- Faulty workmanship – contract work policies specifically exclude damage caused by faulty workmanship.

- Consequential loss – consequential loss is a term to describe ‘indirect’ financial loss caused by damage to a business (or property). This may include loss of profits and/or increased costs, additional legal and professional fees, additional borrowing costs, loss of sales revenues (from the selling of a property below market value), and more. Consequential losses can be covered however it is a standalone insurance policy: “Liability Consequential Loss” insurance.

- Natural Hazards – it is not a given that your contract works policy will cover you for natural hazards. Some insurers offer this as an optional add-on to your contract works policy.

- Existing structures – most contract works policies will only cover the works being built i.e., relating to the contract.

- Third-party damages or loss – this is covered by public liability insurance

- Tools and equipment on site

- Employee theft

- Acts of war

What gets excluded and what gets covered can vary from policy to policy, and it is for builders and owners to figure out which policy works best for their requirements.

Statutory Liability Insurance

Statutory liability insurance protects businesses from any fines and penalties resulting from unintentional breaches of New Zealand laws. This can include breaches of the Resource Management Act, the Building Act, the Health and Safety at Work Act, and other relevant acts. As with public liability, cover typically includes associated legal defence costs relating to prosecution under New Zealand’s legislation.

Examples of statutory liability claims include failure to comply with a resource consent condition, pollution of land or waterways with runoff from the site and building without correct consents.

Set Yourself Up for Success: Consult with ASAP Finance Today

Knowing what your construction insurance policies cover (and what they don’t) is a critical part of reducing project risk. Should you, your contractors, or consultants not have adequate cover in place, you may be vulnerable to significant loss; such losses could undermine the success of your project as well as your business’s ability to operate as a going concern.

As is the case with most things, it pays to research options in the market and to seek professional advice. Engage with specialist financial advisors who have experience in construction insurance and access to a wide pool of products available in the market. Consult with ASAP Finance today!

Navigating a Construction Boom

Property development has been thriving over the past 12 to 24 months. Low interest rates and insatiable demand for housing (from investors and owner-occupiers alike) has spurred one of the most significant construction booms since the 1970s.

The industry that was hit hard during the GFC appears to have now fully recovered with a strong pipeline of projects continuing to work their way through the system. The annual number of new homes consented has been setting new records each month since March 2021. The previous high (last set in February 1974) of 40,025 was surpassed for the first time. While not all newly consented dwellings will get built, it is commonly accepted that a high level of new consents is usually followed by high levels of building activity.

Operating at the coal face of the property development and construction finance market, we can attest to the significant increase in demand for project funding. ASAP Finance has funded over 800 new dwellings year to date, a 57% increase from 2020 when we funded 507 houses. Almost all of our clients have been huge benefactors of the construction boom, and while we expect demand for housing to remain strong into 2022, headwinds are building, and developers need to be mindful of the changing conditions.

It is well established that construction is a cyclical sector of the economy, and one prone to overshooting. Economic cycles are to be expected and can be planned for — it is the extreme or rapid pace of change that so often catches people off-guard.

Characteristics of boom-and-bust cycles within the construction sector are well studied—rapid increases in construction activity can cause inflated construction prices, reduced competition among builders, and result in increased lead times (due to capacity constraints). In contrast, downward moves can result in competitive cost-cutting, a reduced margin, and pressure on quality.

With the above in mind, it is hard to ignore some of the characteristics on display in the current market, creating challenging conditions for property developers and contractors alike. Let’s look at some of these challenges in more detail:

Industry-Wide Capacity Constraints

The industry is facing significant capacity constraints. All sectors of the market appear to be affected by shortages of raw materials, essential products, and skilled labour. The unemployment rate is sitting at a historic low of 3.4% (a rate not seen since December 2007) and issues with sourcing and retaining skilled staff are now commonplace resulting in extended deadlines. This is evident across the development lifecycle from planning to construction.

Local councils, who are essential to project planning, are consistently missing the self-imposed statutory deadlines to process consent applications. Recently, Auckland Council wrote to one of our clients advising them that resource consents are taking 6 weeks to be simply ‘assigned’ to an assessor due to ‘unprecedented demand’ and ‘under-resourced teams’. We have not witnessed a single resource or building consent issued within the 20-working day statutory deadline, with most taking between two to three months to process.

Construction companies are facing similar constraints. With most contractors booking ‘back-to-back’ jobs, the consequences of missing pre-arranged ‘window’ for a sub-trade to undertake specified works is now dire. For example, if you have your slab-pour booked for Wednesday, and for some reason the slab is not ready on that day (say because you had previously failed a pre-pour inspection that required remediation), it is not a simple process of re-booking the sub-contractor for an alternate date. Often, the next available date may be weeks, if not months away from the prior date, significantly pushing out your completion date.

Supply Chain Disruptions

In addition to capacity constraints, importers continue to face considerable disruption to their supply chain resulting from Covid-19. Freight and shipping costs have surged, with the latter reported to have increased as much as 400% since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2019. Limited availability of freight and increased lead times (including increased processing times to clear NZ ports) are only further contributing to price increases across essential products in the construction sectors. The above is of note given an estimated 90% of all (building) products sold in NZ are either imported or contain imported components not easily replaced by domestic supply.

What does this mean? We are hearing of delays on framing, weatherboard, cavity batons, insulation, concrete… the list goes on. While some materials are easily replaceable, others are not with alternate products often only available at a significantly increased cost (if at all). Most recent anecdotes from our clients include 4–6-month delays on frames, 2-month delays on concrete, and other issues.

Escalating Construction Costs

Surging demand and limited supply are leading to rapidly rising construction costs—ANZ reported in Q2 and Q3 2021 an increase in construction costs of 4.5% on a quarterly basis. However, these numbers do not appear to represent the extent of the cost increase prevalent in the industry.

At ASAP, we have witnessed contracted construction rates (from independent builders’) for affordable terraced product skyrocket from $1,900-2,100/sqm in 2019, to $2,500-2,800/sqm today. Developers who have engaged builders on fixed-price contracts need to consider whether their contractor will still be able to perform/complete the project within the agreed budget. Opting for the cheapest contractor in this market (or any market) is not the right strategy — you can expect an increase in variation claims (VO’s) as they try to recoup or pass on the cost for mispricing the job. Worse still, some of the so-called “affordable” builders may not have the cash flow or planning foresight to overcome the pressures brought about by cost escalation and may become insolvent themselves.

The rate at which prices are rising is forcing builders to move away from the traditional fixed-price contract—with a preference to opt for cost-plus-margin or other forms of contract. We are also seeing an increase in contractors seeking upfront payments and deposits to guarantee the supply of materials. The above has flow-on affects when obtaining funding—most banks are unwilling to fund projects without fixed-price contracts.

Furthermore, there are very few lenders who will allow upfront payments that do not reflect work completed on the site to date (as these payments are affectively unsecured). Looking ahead into 2022, relationships with funders who understand such complexities and who are willing to be flexible with the funding mechanics will be paramount.

Funding Market Struggling to Meet Demand

Main banks have tightened considerably over the past 6 months, in response to the mounting headwinds within the sector. We are hearing of banks requiring up to 130% presales cover ratio (vs. the previously accepted 100%) and increased contingencies of up to 20% of the construction budget (previously 7%-10%). In addition, there has been many changes to the regulatory environment in the retail market, making funding generally harder to obtain. These changes include amendment of the CCCFA (responsible lending code), reduction of LVR speed limits, the introduction of tighter debt-to-income ratios, and changes to test interest rates.

As the banks retreated, non-banks stepped up to fill the void (as best they can), however, liquidity appears to be a common issue. Anecdotally, most the major non-bank development lenders have had to pause or limit lending at some point during FY2021—a market characteristic that used to be commonplace but has not been prevalent for several years. Even at ASAP, we were forced to limit the onboarding of new clients in November and December due to unprecedented demand, despite having increases to our funding lines approved earlier in the year. In this environment it’s important to be wary of irresponsible lenders who over-trade—we are already hearing of lenders who are unable to meet settlement obligations or make progress payments under the existing facilities. At ASAP we operate with a margin of safety that ensures we can meet obligations to existing clients.

Limited funding is having flow-on effects regarding loan processing times and credit criteria. Applications are taking longer to process, as non-bank lenders wait to match up new lending with repayments. Expect low-risk transactions and existing relationships to be prioritised ahead of high-risk transactions or ‘new-to-bank’ clients. Developers should expect enhanced due diligence, tougher conditions, higher interest rates and fees, and greater equity contribution. This trend can already be witnessed industry-wide to varying extents; for example, one lender who previously provided development funding without a QS is now insisting on having a QS appointed to every project. To avoid being caught out—engage with your lender as early as possible and take time to work through any conditions up front.

The Path Forward: Consult with ASAP Finance Today

While the issues at play are complicated, they are in essence textbook characteristics of a booming construction market. Partnering with experienced and well capitalised lenders will be key to navigating a path to success. We encourage our clients to engage with us early and get a good understanding of the funding that would be available and also get clarity on the likely terms and conditions. Get in touch with ASAP Finance for property finance in New Zealand today.

Residual Property Valuation – What to Know as a Property Developer

Property valuation is a critical skill that all property developers need to learn. Basic principles of valuation are used when putting together a project feasibility, which is the starting point for many developers when assessing the viability of a new project. The resulting feasibility will dictate the price one can pay for the land, based on a pre-determined margin.

Today’s market is highly competitive and securing land is perhaps one of the greatest challenges that developers face. New entrants and seasoned developers who are looking to scale and capitalise on the nascent demand for housing are driving land prices higher. This is especially for properties that are well located, have services on-site, and have zoning favourable for medium to high-density developments.

It is these transactions that are so frequently caught and publicised by the media. The news cycle are quick to highlight how much a property is sold for compared to its government’s valuation (or CV). For developers, however, a property’s CV plays little to no role in their assessment of value. Instead, what one is willing to pay is driven by a property’s residual value.

The Basic Formula of Residual Valuation Method

The residual valuation method is reductive. First, the developer estimates the total value of each proposed unit in the development. The sum of which is known as the Gross Realisable Value or GRV.

From this figure, expected costs associated with the development, an allowance for profit (and risk), and miscellaneous fees are deducted.

The amount left is the properties residual value, which implies the price a developer can pay to acquire the site. The basic formula for the calculation of residual value is:

Residual Value = Gross Realisable Value – (Total Development Cost + Project Margin + Fees)

Note: All figures should be stated on a GST exclusive basis.

The Process of Calculating Gross Realisable Value (GRV)

GRV is the total value of all units within a development on an as-if complete basis. More simply, GRV is the total sales revenue (less GST) that the developer expects to generate once all the units within the development are sold.

The ‘as-if-complete’ value is driven by the evaluation of comparable units that have recently sold in the immediate area and analysis of current property listings. Input from local real estate agents and other property professionals can also be invaluable.

Property developers spend a significant amount time and effort in assessing how they can maximise a site’s GRV while keeping costs low – this is what will drive a project profitability.

GRV estimations are heavily influenced by the following factors:

Yield

Yield is the number of units the developer is able to build on the property (in accordance with council planning rules.

Typology

Typology is the the design of the product being built. This includes things like the Gross Floor Area (GFA) of each unit, the number of bedrooms, bathrooms and other design considerations.

Yield and typology go hand in hand. A developer will typically run a few scenarios for a given site to see the variable return profiles of each typology. For example, they may look at what will the GRV will look like if you build eight two-bedroom townhouses vs. four generously sized four-bedroom townhouses.

In all instances, the proposed scenarios will need to fit within local council planning rules. A detailed knowledge of planning rules can help uncover a sites true development potential and enable you to move quickly on opportunities as and when they arise. Project consultants including architects and planners are also an invaluable resource.

GRV should not be assessed in isolation – one needs to consider how the final typology mix will impact the total project costs.

Factors to Consider in Calculating Total Development Cost

All project costs need to be carefully considered when using the residual valuation method. Below we have detailed just some of the cost items likely to be incurred by a developer for a typical residential townhouses project.

Pre-development (planning and consenting)

- Architect

- Planner

- Surveyor

- Engineer

- Quantity Surveyor

- Valuers

- Legal + other

Development

- Construction

- Construction monitoring (engineer, quality surveyor)

- Council fees and levies (development contributions, utility connection charges)

- Titling (surveyor & legal)

- Contingency

Sales and marketing

- Marketing

- Sale commission

Finance

- Interest

- Fees

- Tax

Ensuring that cost assumptions are realistic and include an appropriate contingency is a must for the accurate assessment of the residual value. Projects are always susceptible to delays, cost escalations, and other unforeseen expenditures. Allocating extra funds for contingencies in the budget can help reduce the impact of cost escalation.

Changes to a projects’ costs can result in significant changes to the residual value of the property. This is one of the reasons the residual valuation methodology is considered a highly sensitive methodology.

Setting Ideal Project Margins

Project margin refers to the profit the developer expects to earn from the project. For residual valuation method, the developer decides on the return they require in accordance with the risk inherent to a given development.

Larger, more complex property developments come with additional risks and typically require a great return. While for simple projects, a developer may be willing to accept a lesser return.

In the residual valuation method, if a developer increases the margin they require to move forward with a project, it decreases what the developer can afford to pay for the land. In other words, it reduces the residual value of the property. In contrast, if a developer decides they are willing accept a lower profit margin for the project, it will increase the amount they are willing to pay for land.

Today, 20% is widely considered and acceptable profit and risk allowance for typical residential property developments. If you are developing a single residential plot, the margins can be scaled down below 20%.

Applying Residual Method – Example

Consider a proposed development project for an integrated townhouse development.

A developer is proposing to build:

- 10 residential units, 2-bedroom, 1 bathroom, floor area 80 sqm.

- Asking price of $850,000 (expected end value)

- Build cost is $2,600 per sqm

- Subdivision costs (earthworks, drainage, etc)

- Council Contributions, Connection Charges, Infrastructure Growth Charges

- Project margin of 20%

GRV (excluding GST) = $850,000 x 10 = 8.5 million

The total project cost (excluding GST) = 4.0 million

20% Profit and risk allowance = 0.8 million

Land Residual Value = GRV – (Build Cost + Project margin)

$8.5m – ($4.0m + $0.8m)

Residual land value = $3.7 million + GST

Based on the residual valuation method, the above implies that a developer can pay $3.7 million + GST for the land, and pay all costs required to complete the development with an expected return of $0.8m (being 20%).

Make Your Next Move With an Expert in Your Corner

Looking to secure development finance for your next project? Before making your next move in the New Zealand property market, you can consult with an expert at ASAP Finance. Our team can help you in all aspects of property financing—get in touch with us today to learn more.

Managing the risks of cost escalation

The Knight Frank Global House Price Index shows that global house prices lifted 7.3 per cent in the year to March 2021, and New Zealand had the second fastest growth globally with a 22.1 per cent increase. Property developers looking to take advantage of the favourable market conditions have ramped up residential building activity with new dwelling consents annually tracking at their highest levels on record.

This is great for the NZ property market where limited supply has been a key issue for first home buyers and investors alike. A new challenge now presents itself as the construction sector struggles to keep up with the substantial growth.

Labour and material shortages are occurring more frequently, and developers are experiencing delays when ordering material. Inflationary pressures are also mounting across the board, as the global economy continues to recover from supply chain disruptions.

Managing the risk of cost escalation is now front of mind as suppliers and builders raise prices to protect their profit margin. Three basic approaches to risk management can be summarised as follows: Control, Transfer, and Avoid. Below, we break down these approaches in more detail and what they may look like in practice.

Control

Cost-planning: Careful planning at the start of the project is the best way to manage cost escalation risk. Building a robust budget requires engagement with suppliers, contractors, and consultants before committing to the project. Be sure to include a contingency sum into your project budget to cover unforeseen costs. The contingency sum should be adequate for the duration of the project, including possible time delays. Ask yourself, what is the consequence of a 3-month delay at the end of my project? How does this impact my feasibility?

Procurement: Engage with suppliers to identify potential delays when ordering materials. If material supply shortages are forecast, you may need to order in advance to secure stock. This will likely have an impact your cash flow planning. Leveraging long-term supplier relationships, buying in bulk, or seeking alternate suppliers may also be an option.

Redesign or Substitution: Where certain parts of the project work are subject to constraints (being material or labour) or inflationary risk, you may be able to mitigate the risk by redesigning the plans or substituting materials.

We are increasingly seeing construction contracts and building consent documents that allowed for two cladding options. The first, being the preferred cladding solution for the build, the second, a backup solution should the preferred choice not be available due to supply constraints.

Transfer Risk

The Construction Contract: The construction contract is a mechanism for transferring risk. Most infill townhouse projects are done on a fixed price (lump sum) contract. By locking in a fixed price, the developer can transfer cost escalation risk to the contractor. This provides cost certainty for the developer, but often comes at a cost premium.

Be sure to negotiate early with your contractor to eliminate provision sums A provisional sum sets aside money for specific building work when there is not enough detail to provide a fixed price (if an item has not yet been purchased or chosen and the installation cost is unknown). Ask the contractor to confirm whether the quote is appropriate for the quality of goods you are expecting.

The cheapest solution does not always cost you the least! Contractors who are not making their margin may generate claims (variations) to recoup some of their costs. Alternatively, the contractor may prioritise other more profitable jobs ahead of yours, and this can cost you more than if you had negotiated a fair contract from the beginning. In the worst-case scenarios, contractors may end up insolvent, leaving your project in the lurch.

Avoid or Defer

If you are unable to mitigate, control or transfer risk to an acceptable level then the best approach may be to avoid the project or defer it until conditions are more suitable.

Consult with ASAP Finance for Construction Finance Solutions

We are a market leading finance company in Auckland. Our team will help you get your development project off the ground and avoid financial risks. For more informative articles on development finance, subscribe to our Newsletter below and follow us on LinkedIn.

Rates and fees in the Development Finance Lifecycle

Property Finance in New Zealand

“What are your rates and fees?” is perhaps the most frequently asked question by clients approaching ASAP property finance specialists for a construction loan. However, many developers do not take the time to consider how these costs are incurred over the life cycle of the property development project.

Unless you have built a cash flow model for a project, it is not something you will have seen in practice. Cash flow models are not necessary. However, understanding how interest and fees are incurred during the lifecycle of the project is extremely important as it can inform decisions that allow you to structure your debt in a cost-efficient way. This article focuses on interest repayments and the so-called ‘S-Curve’.

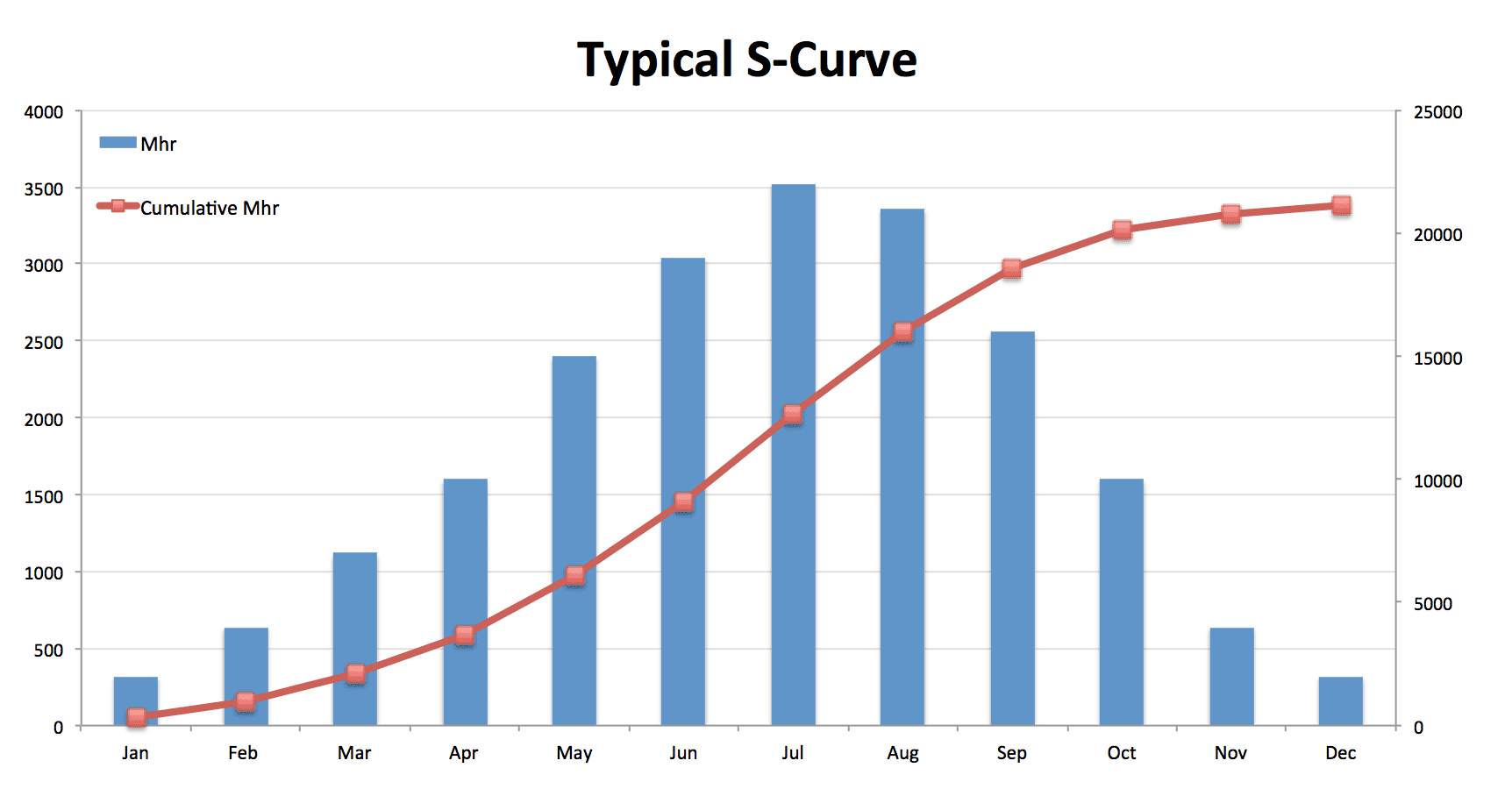

What is the S-Curve?

The S-curve relates to the shape produced by the typical flow of costs on a property development project. Most project costs are not spent linearly (or in a straight-line). You typically start by spending less per month during the early stages of the project (when you are in the planning phase). As you begin construction, costs per month ramp up until they ultimately reach a peak, generally once the project is fully closed in. After which, the total cost per month slowly starts to decline as construction winds down and you await title and CCC. The result, if you graph the cumulative cash outflows, looks like an ‘S’.

Read more about the Ins and Outs of Lender Fees for a better understanding of the so-called, ‘S Curve.’

Why does this matter?

The interest on property development loans is usually calculated on the drawn balance of the loan, i.e., how much money you are actually using (unlike establishment fees and line fees, which are charged against the facility limit).

This is important because funds are drawn down in stages for construction loans. This means that a 10% interest rate does not necessarily translate to a 10% cost. Assuming you draw down funds evenly (and a minimal initial advance) then the interest expense tends to work out to be around 6.5% of the facility limit or 65% of the headline interest rate.

For this reason, the timing of drawdowns can have a significant impact on the cost of borrowing. If a property development has large upfront costs, then it can significantly increase your interest expense. For example, having a large initial advance to facilitate settlement on the land, or using a building methodology that requires you to pay a large deposit to the manufacturer.

Conversely, if you have a project where most of the costs are incurred toward the end of the project, it can reduce your interest expense. When and where delays occur during the life cycle of your project can similarly impact your interest expense. For example, if you experience delays at the beginning of the project (when few costs have been incurred), the increased interest expense will not be as great as if the delay had occurred at the back end of the project when the loan facility is fully drawn.

Reducing your interest expense

- Put your equity into the project upfront. This will reduce the length of time that you are borrowing funds from your lender. Plan your project to ensure that you do not face delays at the end of the project. Waiting for LINZ and the council to grant approvals such as code compliance are perhaps two of the most time-consuming processes. Worse still, is that these delays occur at the end of the project while the facility is fully drawn thereby incurring significant interest costs.

- Titles: Complete works required to obtain individual freehold titles early on in the development. This may require you to upgrade infrastructure, install utility connections, or pour your driveway early. These works generally relate to s223c and s224c which are required to lodge for titles.

- CCC: Ensure that your builders’ bookkeeping is in order and that all necessary producer statements, warranties, and engineering sign-offs are procured from sub-contractors upon completion of works and not at the end of the project.

- Review your construction contract to ensure that there are no large upfront payments. You want your payments to the contractor to reflect the amount of work completed. Not only does this reduce interest costs, but it also reduces your risk to the builder’s financial position. For example, should the construction company be placed into liquidation, any funds advanced to work that has not been completed will likely be unrecoverable. This means you will incur these costs again when you engage another builder.

- Negotiate ‘liquated damages’ with your builder. A daily sum payable by the contractor to you (the developer) for every day that the builder is late delivering the project. These funds can be used to offset the additional interest expense incurred for the late delivery of the project. You may also want to consider an early completion bonus payable by you to your builder, should they finish the project ahead of schedule.

Guide to the National Policy Statement on Urban Development 2020

New Zealand recently adopted a major change in urban environment planning that is expected to lead to significant upturns in the world of property finance.

Gazetted on July 23rd and pushed into effect on August 20th of 2020, the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD) is an evolution on previous government documentation surrounding development in urban areas.

Developed by the Ministry for the Environment and the Ministry of Housing and Urban Development, this new statement contains objectives and policies that councils must give effect to in their resource management decisions.

The NPS-UD is aimed at improving development capacity for housing and business – putting New Zealand communities on the path to well-planned urban areas and ensuring a well-functioning urban environment is created for all. With some 86% of New Zealanders living in urban areas, the need for considered planning rules has never been greater.

For developers, homeowners, and stakeholders alike, the release and implementation of this statement heralds some significant changes to both development capacity and development rates. Understanding the intention behind the NPS-UD 2020 will be key to delivering projects that not only maximise development potential but enhance the urban environment.

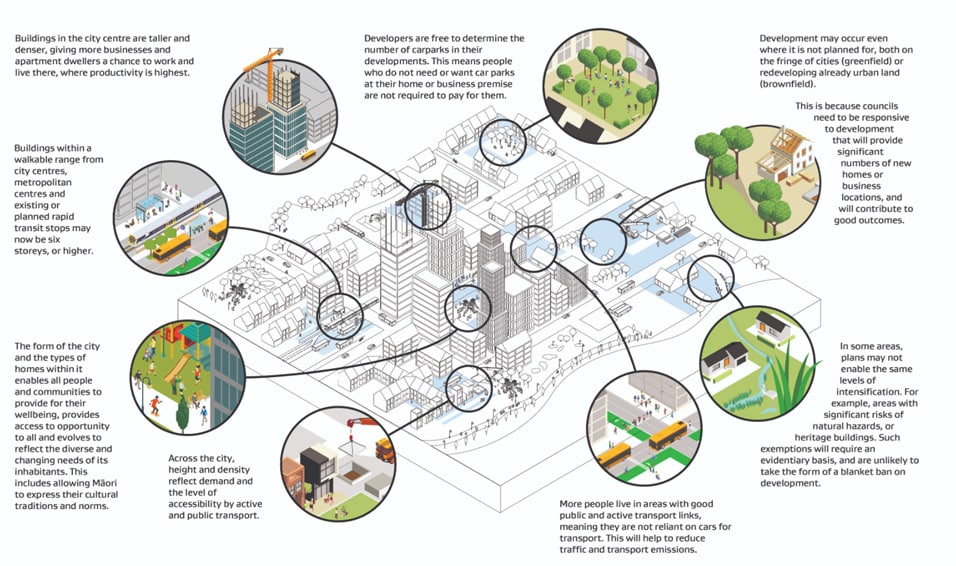

The Major Policy Breakdown for NPS-UD 2020

In simple terms, the NPS-UD seeks to “improve the competitiveness of New Zealand’s urban land markets through greater flexibility in urban policy”. It is wide reaching and applies to all local authorities that have all or part of an urban environment within their district or region.

A targeted approach has been adopted to ensure that policy objectives and planning responses are matched to areas of high growth and base populations. This has been done by categorising territorial authorities into three Tiers; where Tier 1 is comprises the larger cities of Auckland, Hamilton, Tauranga, Wellington, and Christchurch. It is these authorities that are poised for the greatest change.

Most of the provision in the NPS-UD are aimed at developing urban areas in a way that combat high land prices, unaffordable housing, and improved access, however, three are key.

(1) Intensification (Polices 3, 4 & 5)

(3) Responsive Planning (Policy 8)

(2) Car parking (Policy 11)

Other policy’s outcomes more broadly address the ‘who’ and the ‘how’ of the policy package.

will be key to delivering projects that not only maximise development potential but enhance the urban environment.

Intensification (3, 4 & 5)

The intensification policy places minimums on development capacity required to meet expected demand for housing over the short, medium, and long term.

This required territorial authorities to provide land that is plan enabled (zoned), infrastructure ready and feasible.

Expect greater building height and density requirements in urban regions, particularly in areas of high demand (i.e. brownfield development).

One such example is the requirement for Tier 1 urban environments to enable:

“building heights of least 6 storeys within at least a walkable catchment of the following:

- existing and planned rapid transit stops

- the edge of city centre zones

- the edge of metropolitan centre zones”

Intensification policies are essential to the uncoupling of land prices from dwelling prices in high amenity areas. An image of success for this policy would be a city centre with taller, denser buildings, allowing more businesses and apartment dwellers to live where productivity is highest.

Car parking (8)

Territorial authorities will be required to remove minimum car parking requirements; enabling developers to determine the appropriate number of car parks (if any) for their development. With land prices at record highs, the goal of this policy is to enable the private market to determine the highest and best use of land.

At ASAP Finance, we are already seeing a number of projects being planned with minimal to no car parking. These developments have been well located and have had easy access to public transport.

Another sector of the market expected to benefit from this policy is small format retailer, where bulk retailers such as Bunnings and the Warehouse have traditionally enjoy benefited from minimum carpark requirements as they have possessed the scale and balance sheet to acquire larger parcels of land.

Responsiveness (8)

The responsive development policy is targeted toward increasing land use flexibility and improving land supply through greenfield development. This specifically targets areas that are expected to fall within high labour market catchment areas but where the underlying land is not currently zoned.

Councils are now required to consider private plan changes in places where development was not previously planned. This only applies where the said development would increase development capacity, contribute to a well-functioning urban environment, is well connected to transport corridors and other broader considerations that would contributing to a good community outcome.

Strategic planning

In addition to the direct initiatives described above, compliance and reporting regimes will indirectly influence NPS-UD outcomes. Housing and Business Assessments (HBA) and Future Development Strategies (FDS) have been created and are supportive of wider policies. As previously mentioned, these polices concern the ‘who’ and the ‘how’.

Where the purpose of the HBA is to provide information on demand & supply of housing and business land. It also quantifies what is considered sufficient development capacity. The HBA feeds into the FDS which broadly stipulates how councils are to plan for growth.

Evidence and engagement

The final major policy stipulates that councils must provide a strong evidentiary basis to substantiate all development decision making. Notably, these decisions must always be in consultation with local iwi (per Te Tiriti O Waitangi), as well as local developers and infrastructure providers. This will ensure communities are progressing in a way that reflects the ever-changing needs of their inhabitants.

Why change it now, and what is different from the NPS-UDC 2016?

While the NPS-UDC 2016 was created as the precursor to this new policy statement, the objectives and policies laid out in 2016 have not been as effective as projected. An overly constrained development landscape and property market have made it tough for people to build the homes they want, where they want them to be.

Therefore, certain spots in urban environments become more coveted than others, driving up the price, thus making them accessible only to those with a certain level of wealth. These pieces of land are usually located in convenient places with high amenity.

The natural progression of these events is that people below a certain level of wealth have poor access to transport, employment, and social services. This disproportionately impacts on vulnerable communities, showing some major gaps in the thinking that led to the NPS-UDC 2016.

Key changes in the NPS-UD 2020

This new policy is more directive than its predecessor, giving councils clear guidance and oversight to ensure all regions are working toward better urban outcomes. In other words, to make sure cities are built with all people in mind.

Key changes to the policies include:

- a requirement for planning decisions to contribute to well-functioning urban environments (as defined in Policy 1 of the NPS-UD), which is at the core of all the policies in the NPS-UD

- specific reference to amenity values, climate change, housing affordability and the Treaty of Waitangi (te Tiriti o Waitangi)

- a requirement for local authorities to enable greater intensification in areas of high demand and where there is the greatest evidence of benefit: city centres, metropolitan centres, town centres and near rapid transit stops

- removal of minimum car parking rates from district plans

- a requirement for local authorities to be responsive to unexpected plan change requests where these would contribute to desirable outcomes.

Each council will be required to produce a Future Development Strategy, with clearly outlined steps to achieving an urban environment that meets the above requirements. The earliest deadline for the FDS is in 2024.

Implications for Urban Property Developers

“Such collaboration will allow the sector to move beyond the never-ending cycle of sole-planning stages and into the implementation and delivery of developments that shape cities and enable communities to thrive.”

Leonie Freeman, Property Council CEO

With the recent advent of COVID-19, the New Zealand economy has been in a state of perpetual flux. While property developers have not been as deeply impacted as other sectors in New Zealand, this flux has resulted in a certain degree of uncertainty for anyone investing in property.

Now that the NPS-UD has been pushed into effect, Tier 1 local authorities (including Auckland), have two years to implement the intensification policies laid out. They will also have eighteen months to remove all car parking provisions from any plans or developments. However, expect the National Policy Statement on Urban Development (NPS-UD) to influence Resource Management Act consenting decisions immediately.

The door is now open for Kiwi property developers to work collaboratively with their local authorities to meet a certain level of intensification. Similarly, councils will be more likely to approve urban development plans that meet their needs, and more likely to work with the developer to rectify any issues should the plans not quite measure up.

Councils are now required to consider developments in both greenfield and brownfield areas, so long as they could contribute to fulfilling intensification and improve housing outcomes. Car parks will no longer be a requirement, easing development cost and enabling larger buildings and more green space.

It is now up to the private sector to determine how they can have a hand in shaping the future of New Zealand cities. With luck, developers should be able to shift their focus away from the minutiae of bureaucracy and onto the planning, implementation, and construction of buildings that advance New Zealand cities forward. With surety like this, attaining development finance will be more likely. It all comes full circle.

For more information on the NPS-UD 2020 or Future Development Strategies, follow the links below:

- Guidance on Implementing the NPS-UD 2020

- Breakdown of the National Policy Statement on Urban Development 2020

- Introductory Guide to the NPS-US 2020 from the Ministry for the Environment

- Predicted Outcomes from the NPS-UD 2020

- The National Policy Statement on Urban Development Capacity 2016

Get a head start and ride the wave upward. Talk to ASAP Finance for hassle-free development finance.

We are New Zealand’s market leaders in development finance, offering everything from residential property loans to joint venture property development opportunities. We’re all about removing the hurdles in your way. To get your development off the ground, speak to one

We’re all about removing the hurdles in your way. To get your development off the ground, speak to one